Screams and bangs echoed inside Ohio’s largest youth residential treatment center, buried deep in a state forest. A melee had erupted, with fighting in the hallways and between classrooms. Some children rushed outside to grab rocks. A teacher ushered her students into the cafeteria for safety, giving a lollipop to soothe one crying 11-year-old boy.

During the mayhem, another teacher texted her mother, pleading with her to call 911: “Call them. Call mom please.”

Volunteer firefighters arrived first at Mohican Young Star Academy, but waited for police to stop the violence before entering. A cavalcade of patrol cars from multiple departments, meanwhile, rushed to the facility about an hour northeast of Columbus. Some officers arrived within minutes, while others had to drive at least 30 minutes past farmlands to get there.

The April fight involving more than a dozen Mohican residents left many of them, along with staff, with injuries, including a pencil stab wound to one child, according to police reports. Two workers were treated at a hospital, one of them for a concussion, according to medical reports.

“It was chaos. That day, it was the whole campus. There had been brawls before, but this was the whole school jumping,” said Michelle McDaniel, the teacher who moved her kids into the cafeteria. Fearing for her own safety, she resigned in May from Westwood Preparatory Academy, the charter school that serves the youth at Mohican.

The 110-bed facility that aims to treat children with behavioral and mental health problems had survived a state effort to shut it down several years ago over frequent 911 calls, runaways and the use of restraints. With new owners and renewed expectations, the brawl — one of five since November 2024 that drew law enforcement — has fueled doubts among community members, staff and first responders about the facility’s direction.

A year since new ownership took over, some wonder who is keeping youth and workers safe, when and how leaders decide to call 911, and how they communicate with their increasingly anxious neighbors about emergencies on campus.

“Every time there’s a lockdown out there, the people in the town start to panic only because they don’t know what’s going on,” said Bethany Paterson, who runs community outreach programs at a church in nearby Loudonville, where some Mohican youth volunteer.

Police and fire officials, meanwhile, are alarmed about the toll that repeated calls are taking on first responders, department budgets and public safety.

“You should not have to respond to the same facility, you know, two, three times a year, let alone two, three times a day or week,” Ashland County Sheriff Kurt Schneider told The Marshall Project - Cleveland. Schneider’s department gave up jurisdiction over Mohican years ago, but still responds when forest rangers from a state agency that watches over the facility are too far away or need backup.

Reached by phone, one of Mohican’s owners, Marquel Brewer, said they had no comment after The Marshall Project - Cleveland sent Brewer, co-owner Zach Logan, and chief executive Terry Jones a letter detailing concerns expressed by first responders, workers and other members of the community over the facility’s operation.

Fights vs. “riots”

In Ohio, children placed in residential treatment centers arrive from the foster care and juvenile justice systems because few other places can handle their significant mental health and behavioral needs. Roughly 1,000 children are living in about 140 facilities statewide, but understanding what goes on inside is complicated by the number of state and local agencies charged with oversight.

To piece together this past year at Mohican, The Marshall Project - Cleveland reviewed inspection reports from the state agency that licenses residential treatment facilities and incident logs and narratives from law enforcement agencies. The Marshall Project - Cleveland also watched bodycam footage from officers responding to the April brawl, and interviewed four people who work or have worked there.

What emerged was a picture of a facility in transition, where preteen and teenage children, some standing over 6 feet tall, quarreled with each other or between their groups, with feuds that could last for days. Amid the outbursts, kids followed a code of protecting female workers and younger and smaller children. While children routinely pulled fire alarms, sprayed fire extinguishers and broke windows, workers said they struggled to de-escalate and were confused about when and who would summon police.

The fights identified by The Marshall Project - Cleveland were:

-

On Thanksgiving 2024, law enforcement agencies were summoned for reports that a half dozen children were fighting, with some using wooden bedposts as weapons, according to police reports.

-

On Dec. 1, 2024, another fight involving eight children erupted, where they used broomsticks and bricks as weapons and smashed in windows, according to police reports. A popular Facebook account that monitors police radio traffic in the county posted a report of an “active riot” — a common police phrase that doesn’t distinguish between a small-scale fight and a full-on riot. Brewer commented on the post, disputing that it was a riot, noting that four kids had been trying to fight each other and advising that administrators were handling it. He wrote they were working to change Mohican’s past image of a “jail” to a “trauma informed residential facility for treatment.”

-

On Dec. 4, 2024, law enforcement agencies responded to another fight. One child was “knocked out” and another was bleeding, according to police reports. An Ashland County Sheriff’s deputy wrote that he had detained a youth who had “been one of the main kids in the past two riots there in a week” and had kicked two officers. On Dec. 5, Jones, the chief executive, emailed staff, reminding them of the protocols for handling emergencies, and noting: “In an emergency situation, please DO NOT CALL 911 until speaking with”, then listed several members of leadership, underscoring that “prompt and accurate action” could help ensure everyone’s safety.

-

The April 4 fight erupted between youths while teachers were proctoring state exams, which often causes stress in students with trauma and behavioral needs, said the teacher who asked her mother to call 911. She resigned but did not want to be named for fear that it would impact her current job. After a fight broke out in her room, students from a nearby classroom flooded in to protect her, she said. In the chaos, teachers were shoved and punched. The fights rolled and grew across campus, workers said. Some of the youths indicated that there had been some ongoing conflict between individual kids that began in the days prior, according to Loudonville police bodycam footage. Fire chief Dan Robinson, who resigned in August because of staff shortages and burnout, said EMS and firefighters didn’t enter until police could contain the violence. That afternoon, Jones emailed staff, telling them management would review video footage and determine how to prevent a recurrence, adding: “...no staff should ever contact 911 unless I authorize that. If I am unavailable, leadership has been informed to contact either Marquel Brewer or Zac Logan. Staff should never call 911 unless authorization has been given.”

During a surprise visit on April 10, after learning of the fight, the state Department of Behavioral Health reviewed video footage and interviewed staff, documenting a chaotic scene: Students breached classrooms by climbing over low-slung walls, one staff member bore ligature marks on his neck because he was pulled by the hood of his sweatshirt, one youth kicked and shoved maintenance workers, and a staff member struck a youth with a closed fist. The staff member was later disciplined and ordered to undergo additional training.

The state concluded that Mohican had failed to manage the crisis, and by the time of the state’s unannounced visit, nearly a week after the melee, management had not completed its investigation or addressed staff and student behavior.

It wasn’t clear from DBH’s inspection documents how Mohican planned to fix the citations from the April 4 fighting. DBH did not respond to calls seeking further information on Mohican’s compliance, though the department had told The Marshall Project earlier that the agency thoroughly investigates every complaint.

- On June 23, an additional fight erupted, and officers estimated that possibly five youths were injured, including one who may have needed stitches. EMS treated patients at the campus, and Mohican staff offered to take young people to the hospital.

While responding to every request for service is their duty, the frequency impacts fire personnel and the safety of nearby towns, said Robinson, who was overwhelmed with routine false fire alarm calls from the facility during his tenure.

Those alarms have been “drastically reduced,” said Loudonville Police Chief Brian McCauley, after he and Schneider, the sheriff, met with Mohican leadership and after the installation of new alarms that are only accessible by staff with keys.

Mohican administrators “just need to be kept on,” McCauley said. “I don’t want, when there’s pressure, they’re going to take care of it, and when there isn’t, it’s back to the same old, same old.”

“Mom, you don’t need to go back there.”

The current and former workers who spoke with The Marshall Project - Cleveland said the violence they experienced at the facility has damaged their mental health and that of their co-workers.

McDaniel, the teacher, said she told her supervisors at Westwood when she resigned that what she experienced had traumatized her. Before she left in May, McDaniel went down to part-time and could “barely” make it due to her deteriorating mental health, she said. Noting her history with abuse and neglect, she said, “That’s why I’m so passionate about ‘Don't hurt kids,’ because I know what it’s like to be that kid that nobody wants.”

After April 4 and the tension in the facility, one worker — who asked for anonymity for fear of losing her job — said she struggled with going to work each day. She has since started to see a therapist for the first time in her career. “I just really, really love my job. It’s just been so incredibly hard to go there and feel OK,” she said.

Lately, her own children have started texting her at work to check in, she said, one even encouraging her to quit, saying, “Mom, you don’t need to go back there.” And yet, she does, she said, because of the youth who need her.

A former worker, who did not want to be named for fear that it would impact her future job prospects, said she reached a breaking point after the outbreaks of violence. She said she told management, “We don’t feel supported. We want to know how you are going to support us.”

But she said she couldn’t shake one thought: “What’s it take, for somebody to become so severely injured, then it’s really newsworthy?”

Debating when to call 911

After Jones’ December email on the 911 policy, there was confusion among the staff about what to do in an emergency, according to the workers who spoke with TMP - Cleveland. The policy was further complicated because there were two sets of staff, one at the residential treatment center and the other at Westwood.

McDaniel said workers routinely complained about poor cell signal strength in the forest, limiting their ability to call 911. After Jones’ email, she said, she asked her supervisors if she had to get permission before calling police, and was told that she could call if she felt unsafe.

Having a 911 protocol isn’t unusual. Providers have to strike a balance between trying to de-escalate a tense situation and calling police — which brings the risk of a child being arrested, or worse.

Well-run facilities follow a plan for responding to an incident in stages, including consulting a clinical director, before dialing 911, and such policies are up to leadership, often including the owners and the CEO, said Amy Price at Disability Rights Ohio, an advocacy group that investigates complaints about conditions in residential facilities for children and adults with disabilities.

Calling police “should never be the first recourse of any facility,” Price said.

And having to call police at all can be an indication that something has gone awry at a facility, said Caroline Cole, strategic advocacy lead at Paris Hilton’s 11:11 Media Impact, a nonprofit that strives to reform the youth residential treatment industry and helped pass a federal law last year to combat abuse in facilities.

“Once we get to the point of even needing to call 911, it’s too late,” Cole said. “There’s been so many failures along the way.”

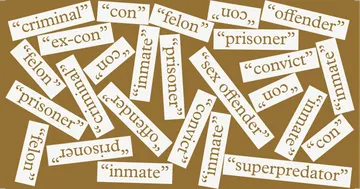

Over the years, some of those facilities in Ohio — and across the country — have dealt with numerous problems, including staff-on-child and child-on-child assault, sexual abuse, improper use of restraints and kids running away.

“We hear caseworkers all the time say they have never seen this level of trauma, self-harm or serious mental illness,” said Scott Britton of the Public Children Services Association of Ohio, a group representing county child welfare agencies.

While the children may have significant needs, experts say, many facilities lack trained staff and appropriate programming to help them. “There aren’t enough employees to do the work, and not everyone has the training or ability to take on these challenges,” said Sasha Naiman, who works on policy reform for youth in Ohio as executive director of the Children’s Law Center, Kentucky.

Over the past year, DBH found Mohican did not have enough staffing to prevent peer-on-peer assaults, which failed to ensure children’s safety. DBH also found training was “ineffective” because staff who had taken it still struck a child and pulled one by the hood. In response, Mohican management said the facility’s staffing “exceeds the required minimum” and noted it serves “challenging youth” that other programs like it refuse to accept.

Mohican officials added they needed to “rethink the types of clients we admit,” noting that could force more children out of state, “tremendously” increasing costs to Medicaid and Ohio taxpayers.

Experts say the hallmarks of effective treatment are good counseling, education, medication if needed, parental support and a range of opportunities for kids to interact with others in the community. They should experience a “good quality of life,” not the “bare minimum,” Cole said.

A community in the dark

What communities near the facility see isn’t what goes on inside, but the emergency responses. For the Loudonville residents and first responders, even one call, especially involving a brigade of police, fire and helicopters, is excessive.

Miranda Taylor, whose Stake’s Shortstop convenience store had been burglarized by one of two Mohican teens who walked away from the facility in March, started an online petition, asking for the facility’s doors to be locked and describing village residents as living “in fear due to abysmal security.”

Afterward, she said, locals would come into the shop and thank her.

“Having a lock on the door, no matter where you are, is a safety measure — for you, who’s inside, and outside,” she said.

On April 4, as police cars rushed past her shop, rumors spread that teens had escaped and were walking down the road from the facility toward town, Taylor said. She called her sister to come get her infant son, who was with her, and a customer with a gun said he would wait in his truck and keep watch.

Jonathan Carter, who lives inside the forest about a mile from Taylor’s shop, said he’s told Mohican youth who pass his property not to go into the woods. He said he and his neighbors used to get courtesy calls when kids walked away from the facility, but that those notifications had stopped in recent months.

Anyone wandering alone at night, let alone knocking on a door, is tempting fate, he said, noting, “Nearly everybody in this county has a gun.”

Paterson, who runs the program at New Hope Community Church where Mohican youth volunteer, said the emergency response unnerves her and the older volunteers who have gotten to know the Mohican students. “There are those who really do want to be a better version of themselves,” she said, referring to the children, but then her mind returns to the “lights and sirens.”

“It doesn’t take more than a few of those instances before public perception gets remarkably skewed,” she said.

McCauley, the police chief, said he wants Mohican to get to a place where “they’re helping the kids and not being such a dysfunctional facility because it’s definitely needed.” He worked at the facility over two decades ago when it was a state-operated juvenile correctional facility. He said kids who are sent to such facilities often get “stuck in the system” and don’t seem to have parental support.

“We need to step up and be the parent and help these kids learn how to grow and be out in society,” he said.