Samuel Herring shuffles slowly, even for a 67-year-old. Tightly gripping a wooden cane in his right hand, he slides into a black leather chair, straightening his posture before retelling his story.

He’s dressed like he is every other day: a rumpled, button-down blue shirt, navy pants and a white knit cap tilted on his head — remnants of his life behind bars, all 39 years and seven months.

And all, he insists, for a crime he didn’t commit.

He was sentenced in 1984 to what amounts to a life sentence for kidnapping and raping Phyllis Cottle, crimes punctuated by blinding her with a knife and forcing her to free herself from a burning car.

Decades later, out of appeals and resigned to dying in prison after several failed parole requests, Herring wrote a Hail Mary letter to the Ohio Innocence Project.

Their review of his case, they say, has exposed common deficiencies that have led to exonerations for dozens of people in Ohio: disparate treatment of a Black man, a conviction won with misleading forensic evidence, historically erroneous cross-racial eyewitness identification and a rush-to-arrest police investigation.

Black people represented over half the 3,200 exonerations through September 2022 in the National Registry of Exonerations. Innocent Black people are almost eight times more likely than White people to be falsely convicted of rape. This racial disparity can largely be attributed to the misidentification of Black suspects by White victims of violent crimes, according to the group. Herring’s case has all those earmarks.

And now, for the first time, the lens of modern science will test Herring’s veracity as well as the resolve of law enforcement long bent on keeping him in prison.

DNA testing is taking place, potentially opening the door for Herring to win his freedom after nearly four decades behind bars.

“I care about what people think,” Herring said. “I want to prove my innocence, regardless if I did all the time (in prison). I want them to know I wasn’t the one who did that. I just want everyone to know I wasn’t the man … They had the wrong guy.”

The work of the Ohio Innocence Project has prompted Summit County prosecutors to agree in October to a forensic review of seven pieces of evidence collected from the Cottle rape: bindings, wire, Cottle’s clothing, a can of car refinisher and a white cloth.

Summit County Prosecutor Sherri Bevan Walsh said her office’s Conviction Review Unit has been working with the Ohio Innocence Project, who first accepted Herring’s case about three years ago.

“We jointly agreed to ongoing and additional DNA testing,” Walsh said in a statement to The Marshall Project - Cleveland and News 5. “We will continue to investigate to ensure justice for Phyllis Cottle’s family.”

The Marshall Project - Cleveland and News 5 contacted more than 10 of Cottle’s relatives. The family declined to comment.

Phyllis Cottle died in 2013 at age 73. But her story endured for years as she devoted her life to advocating for crime victims and those living with blindness.

Her stance on Herring’s release was always clear.

In a 2004 interview with News 5, Cottle, a hobbyist photographer before the attack, called Herring a “creep” and vowed to work to keep him behind bars.

“What is his debt to me?” she asked. “He put me in a prison of darkness for the rest of my life.”

Herring is optimistic a DNA assessment of his case will correct the shortcomings of 1980s-era justice when such forensic measures were not yet available.

Still, he said, his lost years in prison don’t compare to Cottle’s losses.

“Ms. Cottle died hating me,” Herring said, his voice trailing off during an interview at the Richland Correctional Institution.

“It bothers me; it eats at me. I never got the chance to prove my innocence to her. That really eats at me.”

Herring’s continued incarceration comes largely because he’s never budged from his claims of innocence. It’s a message parole board members traditionally don’t want to hear. Herring, like others who appear before the board, was urged to show remorse.

Cottle and her family have consistently shared their disgust over Herring, insisting his repeated denials are proof he has “no remorse and no respect for the human race.”

At a hearing in 2019, Herring told the board he could not take responsibility for a crime he didn’t commit.

As a result, the board determined releasing him “would not be in the best interest of society and would demean the seriousness of the offense.”

One board member, however, tossed Herring some hope, suggesting he contact the Ohio Innocence Project. He did so almost immediately.

Since its inception in 2003, the Ohio Innocence Project has worked to free 42 wrongfully convicted Ohioans. Collectively, the formerly incarcerated had served more than 800 years behind bars.

Nationally, 3,400 wrongfully convicted people have been exonerated since 1989, according to the National Registry of Exonerations.

The Ohio Bureau of Criminal Investigation is retesting the Herring case evidence to obtain a DNA profile. The evidence includes a towel believed to contain semen left by the rapist.

The items used to convict Herring hadn't been needed for testing since his lone appeal was denied not long after his conviction and he had no money or resources to access an attorney.

Mark Godsey, director of the Ohio Innocence Project at the University of Cincinnati Law School, said it was a textbook case of “junk science,” such as fibers and hair evidence coupled with poor eyewitness testimony, that convicted Herring.

“The benefit of hindsight brings new light to this case,” Godsey said. “This is the opportunity to make sure justice is served.”

The Attack

On March 20, 1984, Akron police responded to Wellington Avenue and Myra Street, where Cottle, a 44-year-old mother of three, had just escaped from a burning car.

She told police that a stranger abducted her as she stepped into her vehicle on West Exchange Street. A man pushed a gym bag against her face and threatened her with a knife.

After driving for 10 minutes, they arrived at an abandoned house. The man covered her eyes with her jacket, tied her hands and feet, and took her inside.

All the while, Cottle began mentally noting what she saw: The nearby blue house adorned with an eagle ornament and the green carpeting and dresser inside the house where she was attacked.

After the assault, Cottle said she was forced to empty her purse on the floor so the attacker could take her few bills and coins.

He then made her rip a check from her checkbook: “Now I have your address if you go to the police.”

After Cottle got dressed, she said the man tied her feet with wire and told her to keep her eyes shut as they made their way back to the car. As he drove, he promised to set her free if he got cash.

They visited several banks to withdraw cash, but a teller became suspicious at the second bank, asking Cottle and the rapist to come inside.

Instead, Cottle said the attacker drove away.

While driving, the man forced Cottle to perform oral sex again. He then took her inside the same vacant house and raped her again. He gave her a towel to clean herself.

The man then put Cottle in the car and drove around again. He told her he would let her go if she didn’t tell the police.

She said the man drove to Wellington Avenue and Myra Street. He again tied Cottle’s wrists and ankles. Becoming increasingly angry and frustrated, the man said: “You’ll go to the police. They’ve all lied to me. They all went to the police.”

He then poured something that Cottle said smelled like Pine-Sol in her underwear and started to choke her. The attacker then punctured her eyes with a knife. Cottle was left blind, forever unable to identify the man.

Now alone in the car, she heard her attacker starting a fire. The smell of smoke soon permeated. Once she believed he was gone, she escaped.

‘Blue House with an Eagle on the Gable’

In the hours after the attack, detectives could only rely on Cottle’s memory. She told police the attacker was “clean-shaven” with “no beard and no mustache,” according to police reports.

She offered one key detail: The blue house with an eagle ornament across from the vacant home.

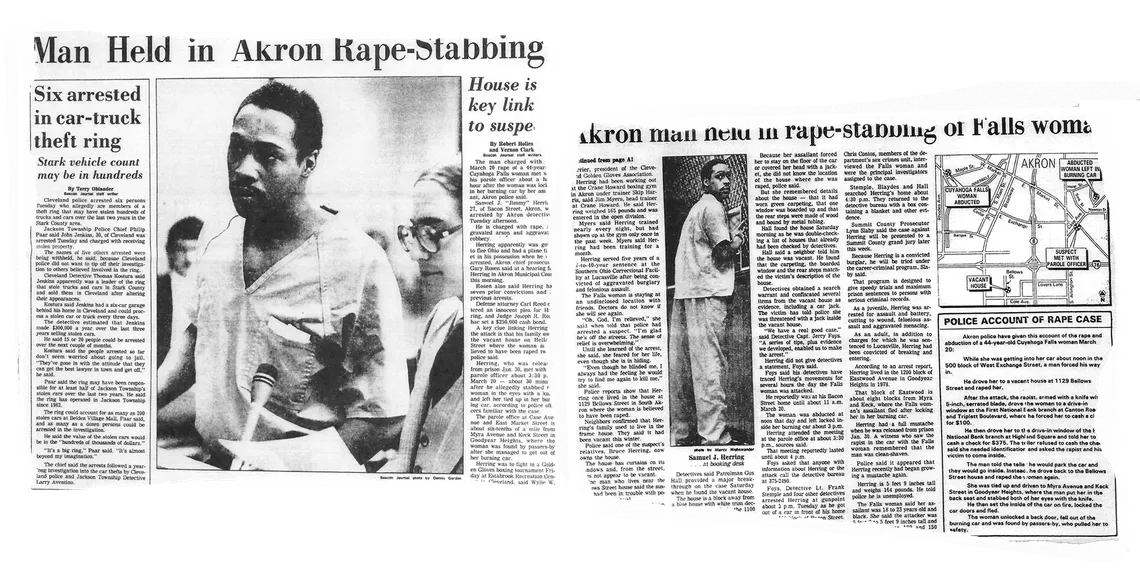

Newspapers splashed details of the crime and the desperate search by police for a crime scene. Police promised the public an arrest would be made, and soon they would deliver Samuel Herring.

After watching TV reports about the crime, a bar manager recalled seeing a Black man running down the street near the area where police first encountered Cottle. The man, according to the bar manager, ordered an orange juice before calling a cab. She said the man “appeared nervous.”

Police contacted the cab company and learned the man was left near the local parole office.

The next day, investigators visited the office to see if anyone matched the attacker’s description. Parole officials said Herring visited a day earlier at 4 p.m.

Herring voluntarily went to the police station later that day, wearing a “neatly-trimmed mustache which was at least a week old,” court records show. He also carried a gym bag, which did not match the description of the one the attacker used to push Cottle in the car.

Police asked Herring for his whereabouts on the day of the attack. He said he slept in, watched television and visited the parole office at 3:45 p.m. He then took a bus to the welfare office, but it was closed. His brother, he recalled, gave him a ride to the Howard Crane Boxing Gym, where he was training for an upcoming fight.

Herring was cooperative, and police quickly ruled him out as a suspect, records show.

But detectives did a U-turn when they finally identified the blue house.

Detectives discovered it was near an abandoned house they eventually confirmed to be the site of the rapes. The house was owned by the Herring family.

Herring later returned to the police station and allowed a detective to take a Polaroid photograph and test a red stain on his jacket that would turn out to be paint.

Later that night, the bar manager and a patron viewed photos of suspects, and each said Herring’s photo looked close to the man who called the cab. Both also pointed out that the man they saw in the bar did not have a mustache.

On March 27, the cab driver said Herring was the closest to the passenger who was in his car. Police later met with Herring at his home on Bacon Street and found speaker wire and a knife — but neither matched those used in the Cottle attack.

‘Career-Criminal’ Trial Program

Herring had several convictions and prior arrests before the Cottle attack. After serving time for a shooting and aggravated burglary, he was paroled Jan. 30, 1984, just months before the rape.

Summit County Prosecutor Lynn Slaby charged Herring under a law designed to give speedy trials and maximum sentences to people with serious criminal records, the Akron Beacon Journal reported.

During the trial, prosecutors relied on a forensic expert who performed tests on material found at the crime scene. None produced significant results.

The criminalist found semen on a white fabric, but the chemical poured on Cottle destroyed the sample. The expert also tested the withdrawal slips from the bank, but neither matched Cottle or Herring.

The state tied Herring to the crime through the expert’s analysis of hair and fibers from Herring’s jacket, the bandage used to bind Cottle and debris collected by a vacuum in the vacant home.

The forensic expert concluded that several fibers from the jacket matched fibers from a piece of Cottle’s clothing to a degree of “scientific certainty.” He said other fibers and hair matched as well.

Three months after the attack, jurors convicted Herring of kidnapping, rape, aggravated robbery, felonious sexual penetration, felonious assault, aggravated arson and attempted murder. He received the maximum sentence of 15 to 330 years behind bars.

Over the ensuing years, police and prosecutors promised to keep Herring in prison until his death, even trying to block his efforts to be heard by the parole board.

In her 2009 newsletter, Walsh, the Summit County prosecutor, called it outrageous that Herring and others won parole hearings as the result of a lawsuit.

“We will stand with Ms. Cottle and other victims to keep brutal criminals like Herring in prison where they belong,” Walsh wrote.

Slaby, the Summit County prosecutor at the time of the Cottle attack, told The Marshall Project - Cleveland and News 5 that he was unaware that DNA testing was currently underway.

He cautioned that prosecutors don’t rely on only one piece of evidence to convict people.

“Next to Jeffrey Dahmer, it was probably one of the (more) heinous crimes we had,” Slaby said.

Godsey, of the Ohio Innocence Project, said the evidence used to convict Herring in 1984 would likely lead to an acquittal if the trial occurred today.

“When one examines Herring’s conviction by today’s standards, the evidence used to convict him was extremely weak,” Godsey said. “The eyewitness statements have all the earmarks of misidentification seen commonly in cases of wrongful conviction.”

‘I Was a Creep Thief’

During two interviews at the Richland Correctional Institution, Herring didn’t shy away from his prior convictions. He stressed those crimes did not involve sexual offenses.

In the years after entering prison for the rape, Herring admitted he wasn’t a model prisoner, largely because of resentment he felt toward the legal system. The rage, he said, festered until he contracted spinal stenosis in 2012.

He credited the compassion shown by prison hospital staff for changing his outlook.

“I woke up paralyzed from my chest down,” he said. “I saw people in Columbus who worked to bring me back, and that gave me a change in my heart.”

Herring knows his case will likely stoke anger when the public learns DNA evidence could prove his innocence. He wants the Cottle family to find peace and stressed he holds no hatred toward them.

“I think they would want to know the truth, just as I do,” Herring said. “I truly, truly, truly hurt every time I see (the Cottle family) on TV talking about me. If it was something I had done … I don't think it would even bother me, but it just wasn’t true.”

Now, Herring has renewed hope and dreams of walking out of prison. If that day comes, he wants to live out his life with his six kids and 27 grandchildren. But nothing, he said, can undo the failures that changed his life.

“If this DNA comes back … and proves me innocent, what will everybody have to say then?” Herring asked. “Can you give me the 40 years back? Can you give me that back? I’m talking about 40 years, not four, not five years, 40. My whole life.”