Over the past 15 years, the number of incarcerated juveniles in the U.S. has plummeted from about 76,000 to fewer than 36,000. Youths who were once sent away to reformatories, training schools, and other large, prison-like facilities are increasingly being offered alternatives closer to home, such as electronic monitoring, probation and counseling.

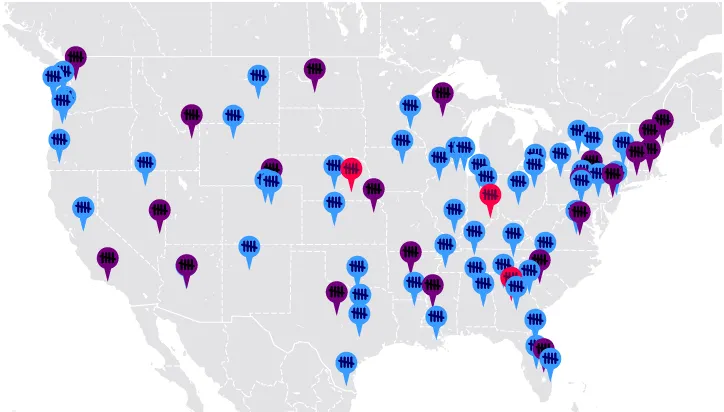

Still, about 80 of those big, aging institutions remain open for business, according to a report released Thursday by Youth First, an organization that advocates less punitive treatment for juveniles. This map pinpoints each prison’s location.

Youth First and other advocates want the facilities shut down entirely. But not everyone agrees that’s realistic, or even desirable. Here are five quick questions and answers that explain the debate:

1. How is a “youth prison” different from other facilities?

Operated by states rather than counties, many of the institutions have more than 100 beds. They are typically prison-like, with locked doors and razorwire fences, a remote, rural location, solitary confinement, inmates with sentences measured in years instead of months, and staff whose job it is to provide security, not education or therapy. Often, the facilities are very old — the Youth First report includes dozens that have been in existence for more than a century.

Juvenile detention centers and residential treatment programs, meanwhile, are smaller, county- or locally-run facilities that hold minors for shorter periods of time, like adult jails.

2. Are some states already shutting them down?

States including California, Texas, and Missouri, as well as New York City, have moved away from this type of prison, opting instead to place more youth in smaller, local facilities and programs. At least four other states (Virginia, Illinois, Connecticut, and Wisconsin) are considering closing down their own largest institutions.

According to the Sentencing Project, America’s largest juvenile prisons (those with a capacity of more than 200) are decreasing in population faster than any other type of juvenile facility.

3. Why should we close youth prisons?

Advocates contend that these prisons are archaic. Any large, remote, anonymous institution, they say, is antithetical to what has been learned in recent decades about the adolescent brain.

The prisons are geographically isolated, making it extremely difficult for juveniles to maintain relationships with people back home, remain engaged with their schoolwork, or keep up with the social and recreational activities they used to love — all of which can reduce delinquency. In these facilities, youths are exposed to a harsh, lifeless physical environment, solitary confinement, antisocial peers and high rates of violence and sexual abuse, stunting their ability to trust, engage, and learn.

Marc Schindler, the former director of Washington, D.C.'s juvenile justice agency and now the executive director of the Justice Policy Institute, says the research shows that what most teenagers need most is a stable relationship with someone they can count on. “And it's absolutely impossible to establish that in a large, anonymous, coercive institution where there's always violence going on,” he says.

4. Why shouldn’t we shut them down?

Elected judges and policymakers, who see their responsibility as keeping the community safe, believe they need to send some violent offenders to secure buildings far away. For many officials, it’s not clear there are any alternatives that serve public safety in quite the same way.

“Historically, a lot of kids have been locked up in these larger institutions because judges don't have other places to send them,” says Anne Nelsen, a former juvenile corrections administrator in Utah and the president of the Council for Juvenile Corrections. “Are we sure that such alternatives are now available everywhere, including in rural areas?”

Shutting down youth prisons is a nice idea, she says, “but I'm focused on making sure kids get the services they need at the places that do exist.”

5. Does it save money to close youth prisons?

There’s no easy answer. Many states have considered it cost-effective to house everyone in one place rather than spending on a network of local, individualized services. And the alternatives to prison that advocates propose, such as counseling, drug treatment, anger management, family therapy, and community centers, can be expensive, at least in the short term.

But because of the decades-long drop in juvenile crime, many of the oldest, largest prisons now have unfilled beds, jamming up the per-inmate price tag of running them. That’s why Virginia’s juvenile justice agency now spends almost 40 percent of its budget on two facilities that house only 10 percent of the juveniles in that system.

“You hear all this talk of saving money by incarcerating fewer people,” says Liz Ryan, president of Youth First. “But what states need to realize is that all those savings don't materialize until you actually start laying off staff, turning off the utilities, and, finally, closing down these prisons.”