The recent wildfires in northern California have consumed more than 201,000 acres of land and resulted in at least 42 deaths. In response, the state’s fire agency, CAL FIRE, has mobilized more than 11,000 firefighters. Of those, 1,500 were inmates from minimum security conservation camps run by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, where they are trained to work on fire suppression and other emergencies like floods and earthquakes.

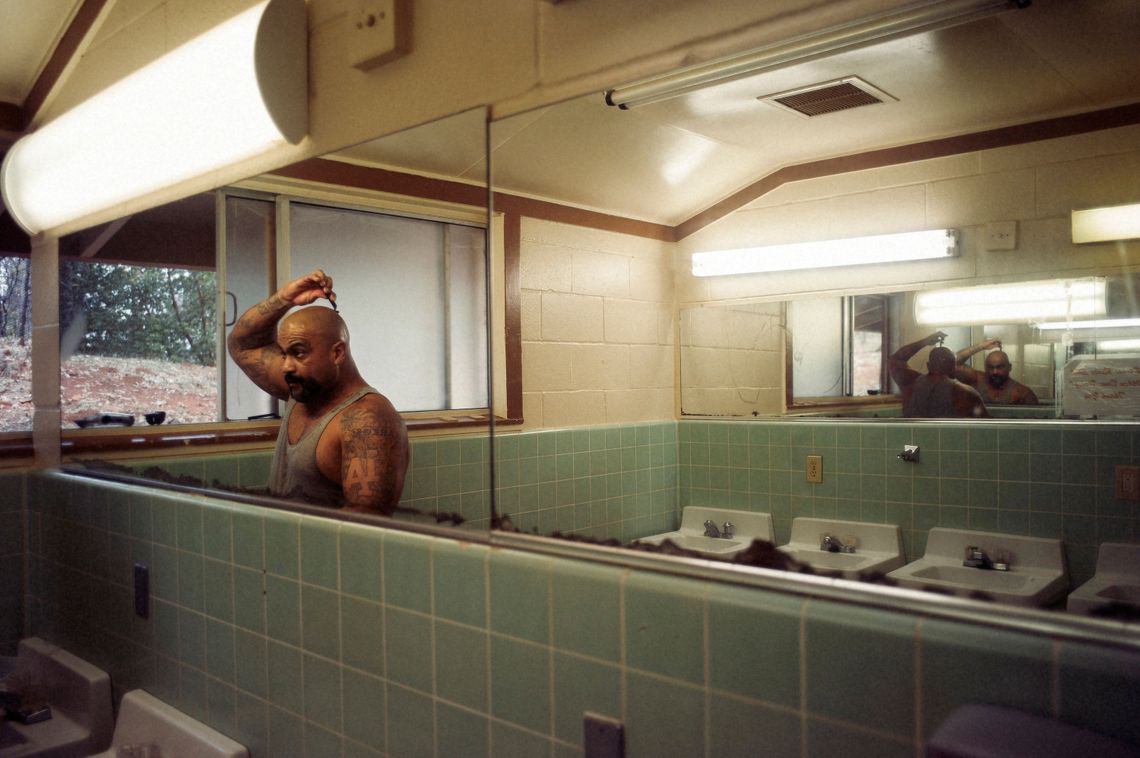

Carlos Marin shaves his head in a slow moment between jobs at the Growlersburg Conservation Camp in November, 2016. Roughly 3,800 inmates in the state’s prison system are on the front lines of active wild fires this fall.

Brian L. Frank

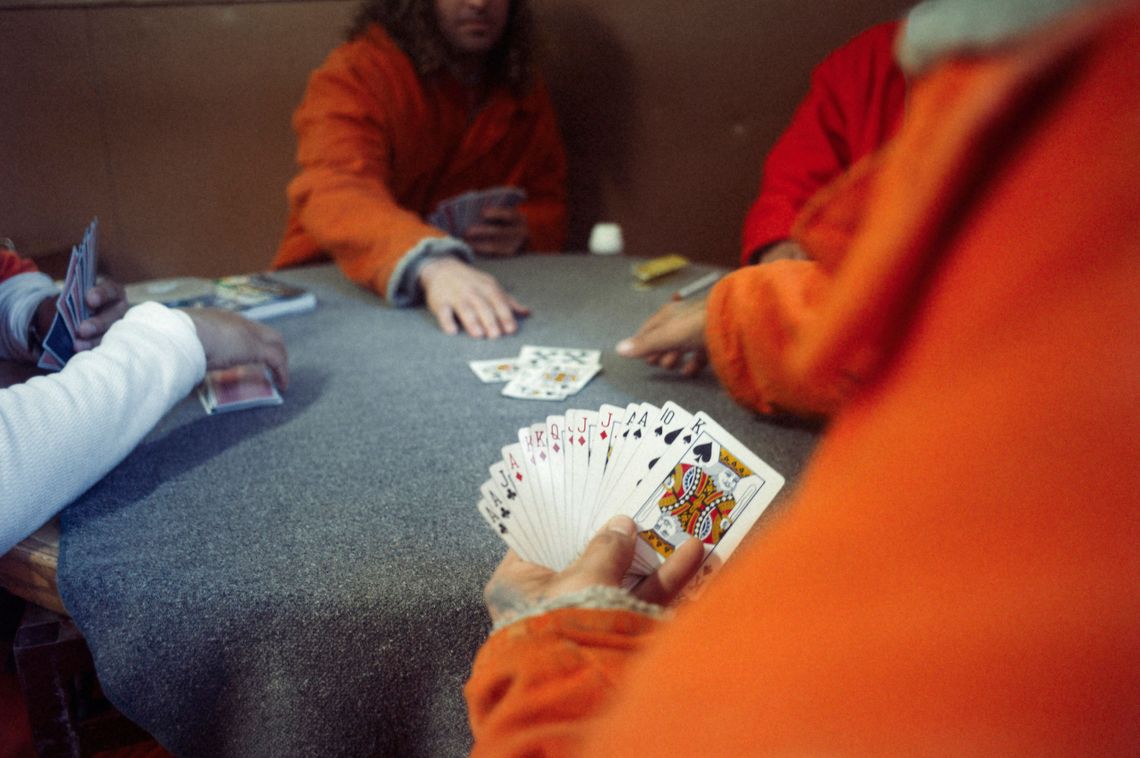

The photographer Brian L. Frank has covered the conservation camps for the past year and lives 10 minutes away from Coffey Park, a Sonoma County neighborhood that sustained heavy damage from the wildfires. He has captured images of the inmates as they handle emergencies but also during their downtime studying for a GED, playing cards, and lifting weights to maintain the physical fitness needed to fight fires.

Although weights have been banned across the California prison system, a special allowance is made for inmate firefighters to have proper gymnasium equipment, because firefighting demands a high level of physical fitness.

Brian L. Frank

Last week, Frank went to photograph the men from the state’s Antelope Conservation Camp as they worked to put out the fire in the Oakmont neighborhood of Santa Rosa.

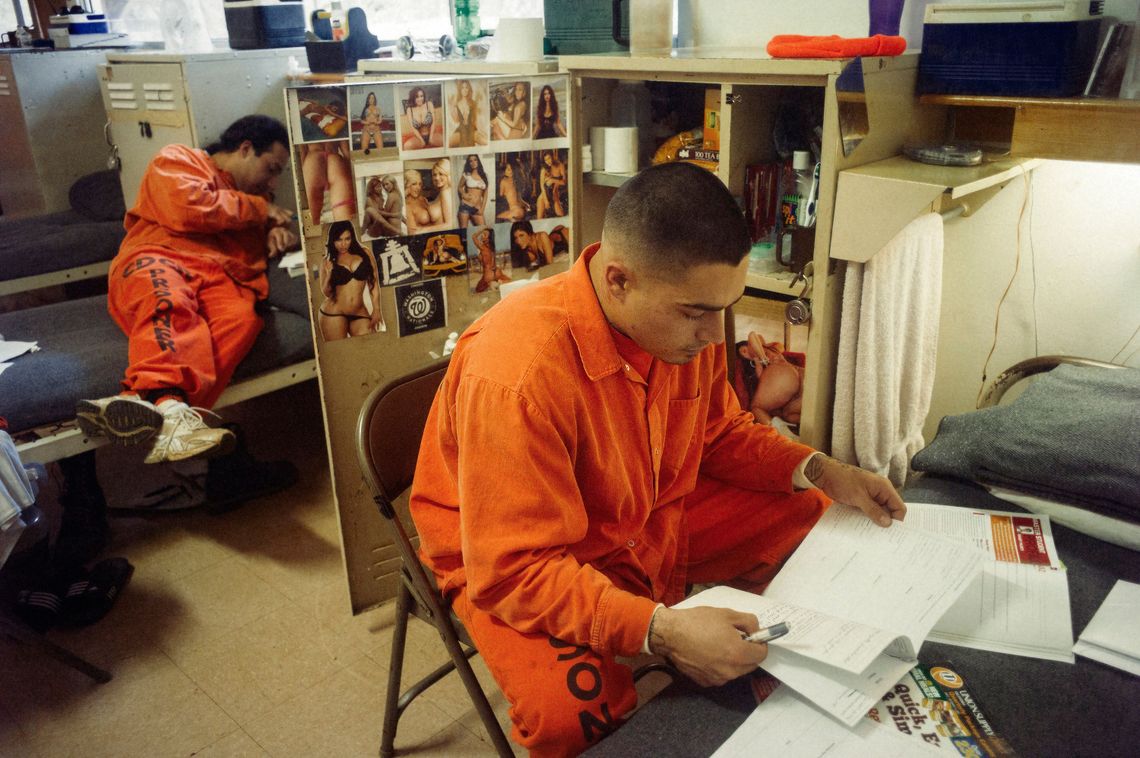

Although there is a high level of cooperation among different ethnic groups when working as a team on the fire line, some areas at the conservation camp itself, such as this "Latino TV room," remain segregated in order to avoid racial tensions or violence.

Brian L. Frank

“They work just as hard as any hand crew doing the dirtiest, hardest part of firefighting,” said Frank. “They do the brutal, backbreaking part of digging fire lines and clearing fuel out of the path of a fire—the thankless work.”

The Antelope fire crew marches into action in Sonoma County, Calif. Much of a crew's work is done by cutting lines into burning brush with power tools so that water lines can be brought in to douse the fire.

Brian L. Frank

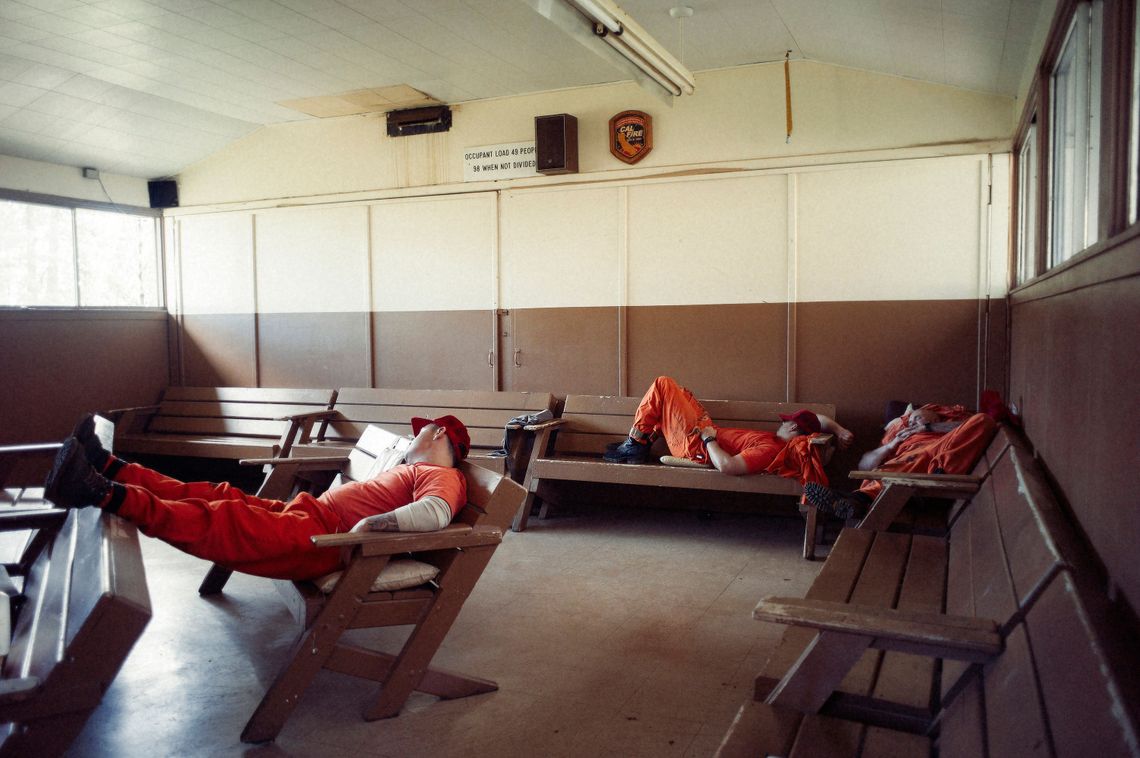

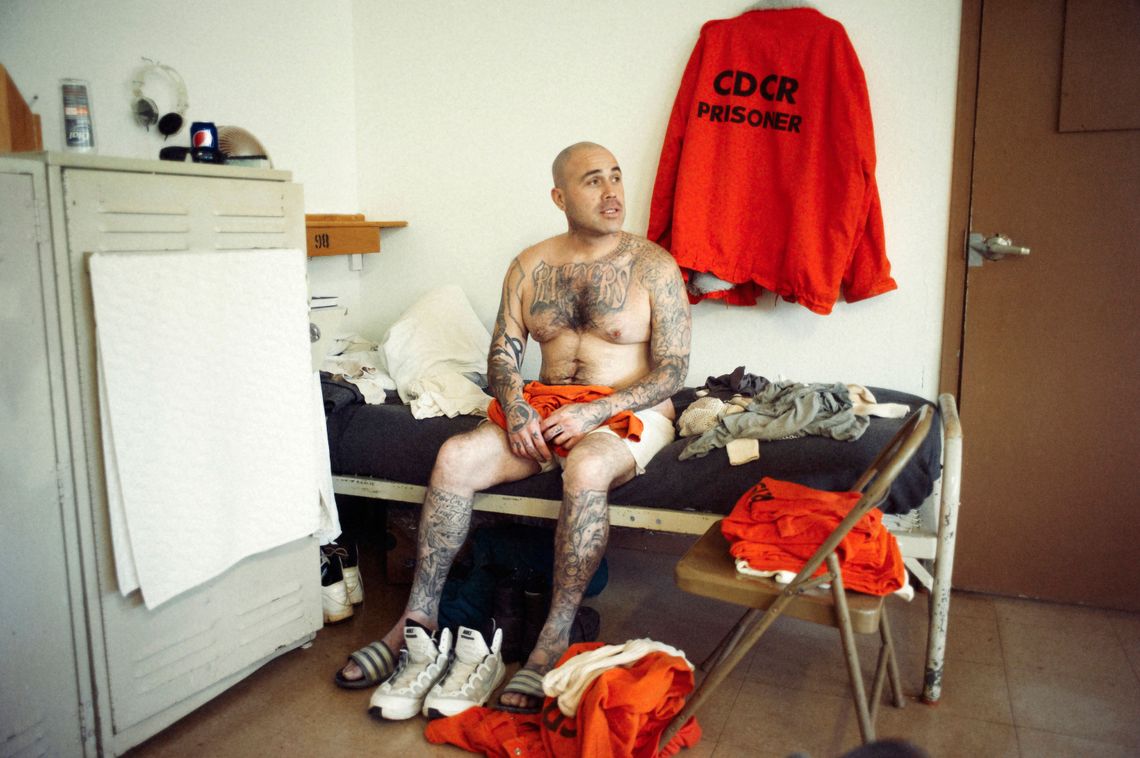

There are 43 conservation camps in California for adult offenders, and 30 to 40 percent of CAL FIRE’s firefighters are inmates from the camps. The inmates work 24-hour shifts, often sleeping in the wilderness, then get 24 hours of rest before heading back to fight fires. Most inmates in California get a day off their sentence for each day of good behavior. Inmates in the firefighting program get two days off for each day they’re in the conservation camps.

A percentage of inmates must remain dressed, ready and on-call for fires at all times, because they can be called at any time by CAL FIRE to assist on a fire or a medical emergency.

Brian L. Frank

The fires in Northern California are now close to 98 percent contained, thanks in part to 3,800 inmates from the state prison system’s conservation camps who have been fighting fires statewide over the last two weeks.

Prisoners earn credits to reduce their sentences by performing maintenance on the camp and working in the community.

Brian L. Frank

Dominic Hernandez, a chef by trade, works in the conservation camp’s kitchen when he is not on the fire line, fighting fires.

Brian L. Frank

Inmates are encouraged to finish studies while they are serving their time, and many spend their time between fires working toward a GED or studying college courses.

Brian L. Frank

Without access to cell phones or the internet, the sole link with loved ones on the outside world at inmate firefighter camps are pay phones.

Brian L. Frank

Inmates at California’s fire camps are allowed more recreation time and more freedom to interact without supervision in the downtime between fires than they would have at a traditional prison.

Brian L. Frank

Inmate firefighters line up to deploy for a day's work at Growlersburg Conservation Camp in November, 2016.

Brian L. Frank

Antelope Conservation Camp firemen are led in formation by a CAL FIRE captain during October’s fires in Sonoma County. The inmate firefighter camps have their origins in the prisoner work camps that built many of the roads across remote parts of California in the early 1900's.

Brian L. Frank

Inmate firefighters from the Antelope fire crew take a breather while carrying gear off of a burning hill during the wine country fires.

Brian L. Frank

Eduardo Amezcua puts out a hotspot while Jon Hooker, standing with a chainsaw, looks on.

Brian L. Frank

Inmates work 24-hour shifts when on a fire, often sleeping in the wilderness.

Brian L. Frank

Eduardo Amezcua, exhausted from fighting wildfire in Sonoma County, takes a break on the side of a fire trail.

Brian L. Frank

The sun peeks through smoke in the wilderness of Sonoma County while much of the area burned with wildfire.

Brian L. Frank

Brian L. Frank is a Catchlight Fellow working in collaboration with The Marshall Project.