Earlier this week, NPR reported that more than one-third of homicides in America go unsolved and examined why police investigators don’t close more murder cases. The Marshall Project asked Thomas Hargrove, the founder of the Murder Accountability Project and murderdata.org, to talk about what he’s learned in a career of studying data on homicide investigations across the country. After 37 years as an investigative reporter, Hargrove recently retired from journalism, to “spend my remaining time and energy to improve the accountability of unsolved murders.”

How did you get started studying murder data, and what has that entailed?

For many years, I was an investigative reporter for the now-defunct Scripps Howard News Service. (I just recently retired as a national correspondent for its successor, the Scripps Washington Bureau.) I happened to see a copy of the FBI’s Supplementary Homicide Report for 2007 and was intrigued to see demographic information for every murder victim in America. I lobbied my bosses for three years that it might be possible to teach a computer how to spot likely victims of serial killers using this publicly available database. Then-Washington Bureau Chief Peter Copeland gave me a year starting in early 2010 to lead a national reporting project we called “Murder Mysteries.” We started by studying the mountain of unsolved murders, which at that time numbered 185,000 committed since 1980. That number now stands at more than 211,000. We found that murder clearance rates vary alarmingly from city to city and that knowledgeable criminologists blame horrendously poor clearance rates on a failure of will by local political leaders to make homicide clearance a priority.

We kept plugging away at the problem of serial murder, finding dozens of methods that do not work. We focused on the 48 known victims of Seattle’s Green River Killer, Gary Leon Ridgeway. We finally developed a method using a statistical technique called cluster analysis, in which we organized individual homicides into more than 10,000 groups of victims of similar sex, age, geography and method of killing. We found hundreds of clusters of highly suspicious killings. Ridgeway’s victims formed only the third largest cluster among women. We started contacting local police departments asking if these clusters could be the work of serial killers. Most quickly agreed that known serial killings were included in their clusters. In some cases, we detected unsolved serial killings known by police but never reported to the public. Two law enforcement agencies began investigations after learning of our algorithm’s findings.

One of the largest clusters was a group of 15 women who were strangled in and around Gary, Ind., starting in the 1990s. We contacted the Gary Police Department and were assured there were no unsolved serial killings in their jurisdiction. We sent them several letters naming the victims and suggesting two apparently distinct patterns, that many young black female victims were found strangled in abandoned properties and that a smaller group of elderly black victims were found strangled in their homes. Gary authorities, including the now-late mayor, refused to talk to us about the possibility of unsolved serial murders in their city. The case was finally resolved (at least partially) in October 2014 with the arrest of Darren Deon Vann, who was arrested after police found a dead women in his Hammond, Ind., hotel room. Vann took police on a tour of abandoned buildings in Gary where he showed them six more female bodies. He told police he’d been active since the mid-1990s.

What is the Murder Accountability Project, and what do you want to achieve?

We are a new nonprofit group seeking to improve public awareness of the problem of unsolved homicides and to make FBI murder data more widely and easily available to police, journalists and the general public. We also seek to improve the quality of reporting by police, using Freedom of Information laws to obtain important information that many major police departments decline to give the FBI in the entirely voluntary Uniform Crime Report and Supplementary Homicide Report. Finally, we operate a website, which will present the findings of our research and make FBI data easily available.

What have you seen in the data about murder itself? Have the means, the motives or the victims changed over the years?

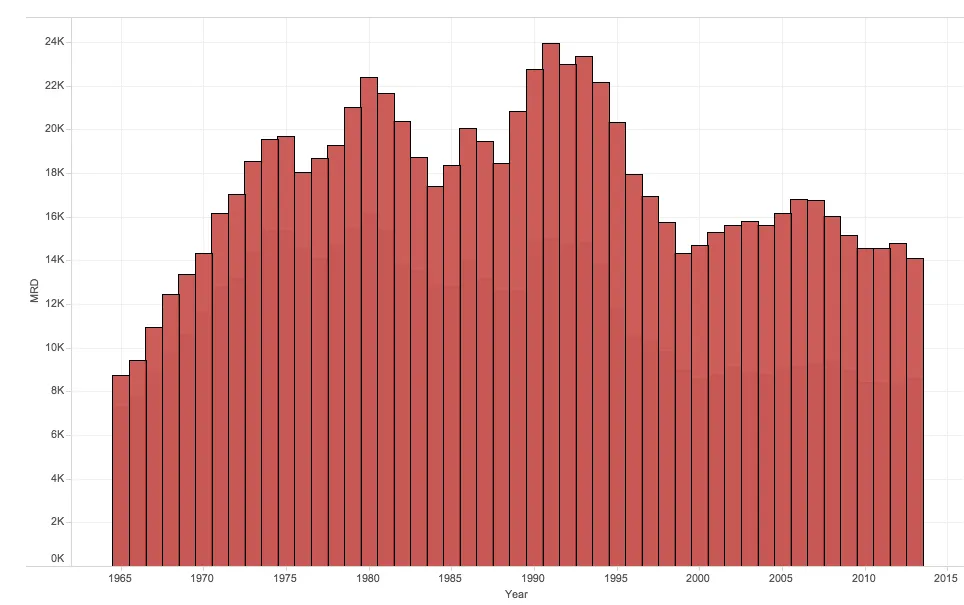

Internet users can see the grand patterns in homicide at the Murder Accountability Project’s website. They also can download FBI raw datasets as well as the results of more than 21,000 homicides not reported to the FBI, but obtained by the Project under Freedom of Information Act requests. The total number of murders has declined since hitting a peak in 1991. There have been few really significant changes in the nature of victims other than a decline in so-called “crimes of passion,” which are mostly domestic violence. Since the Murder Accountability Project focuses on unsolved homicides, the motives in the cases we focus on are unknown.

According to stories by NPR this week, 50 years ago, one in 10 murders went unsolved. Today, that number is more than one in three. Why is this happening, and what have you found in your analyses and reporting that can help explain this?

If readers looks at the “murder solution curve,” they will see that clearance rates have declined significantly since 19651 and have generally stabilized, with clearance rates in the mid 60-percent range in recent years. This, of course, is an unacceptable rate of clearance. That means every year, about a third of killings go unsolved. Every year, more than 5,000 killers get away and are still walking the streets. In Canada, by contrast, the Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics reports in recent years that about 75 percent of the nation’s 500 to 600 homicides are cleared each year, although that figure has varied from year to year. Canada reported clearing more than 80 percent of homicides as recently as 2002.

It is the position of the Murder Accountability Project that declining homicide clearance rates are a failure of leadership by local police and by the politicians over them. When mayors and other elected officials make murder clearance a priority, as did the mayor of Philadelphia a few years ago, the clearance rate will improve significantly. If readers look at the “clearance rate” charts at our website, they will find hundreds of police departments that are doing a stellar job solving murders. Many police chiefs have refused to allow drugs and gangs to take over their city. They have crafted new responses to these challenges that reversed the “murder curve” in their towns.

One theory for dropping clearance rates was the shift in policing strategies toward preventative policing and away from solving crimes. What do you think of that?

We have no data, one way or the other, on policing strategies. We generally endorse the notion that preventative measures to combat crime are wise. But we strongly believe that failure to solve murders are a failure of will by local leaders to make homicide clearance a priority in their communities.

David Simon, whose years as a street reporter in Baltimore led to a couple of books and "The Wire" (and who is on The Marshall Project's advisory committee), argues — most recently in a conversation with President Obama last week — that the war on drugs did grave damage to policing, at least in his city. It became so easy to pump up arrest stats by busting people for possession — and to earn overtime making numerous court appearances — that a lot of police talent was diverted from more serious, hard-to-make cases. How have you seen drugs affect murders and how they’re investigated?

We have no specific information on Mr. Simon’s analysis of Baltimore policing policies. We can see in the FBI data, however, that many communities allowed homicide clearance rates to tumble when gangs began organizing to sell drugs. Homicide investigations are expensive and time consuming. Many cities have opted not to make homicide clearance a priority, a decision made by local leadership.

Another theory is that police are biased against fully investigating the killings of young black men, because 1) they perceive that individuals within these neighborhoods will not cooperate with police, and 2) they recognize that young men of color who are killed are often also perpetrators of violence. This makes the victims less sympathetic and so their killings are not aggressively investigated. In many cities, we’ve seen a deepening mistrust between police and communities — including an informal "no snitching” rule. Does that make it harder to clear cases? What have you examined in the data that might relate to this theory?

As you can see in the data at MurderData.org, about 35 percent of murders of black men were unsolved (no identification of the offender at the time the case was reported to the Supplementary Homicide Report) compared to 28 percent for murders of white men. That racial disparity has grown over time.

In the 1980s, about 27 percent of the killings of both black men and white men were reported to be unsolved at the time of reporting to the FBI. But from 1990 on, 29 percent of white male killings were unsolved compared to 38 percent of black male killings. Why the difference? Some criminologists point to the rise of drug- and gang-related violence in the murder statistics. These kinds of killings are certainly more difficult to solve. But there are many, many police departments where the clearance rates between white and black victims does not show this kind of disparity. It is most likely that the failure of solve homicides is a failure of will by local leadership. Police and community leadership in tandem has demonstrated in many communities that the “no snitching” rule can be overcome by compassionate leaders.

Has better science (DNA, forensics, cameras or testing) helped police. or has it, in some counterintuitive way, helped those trying to break the law? Were certain types of murders more likely to go unsolved in previous eras of police technology?

That homicide clearance rates have plummeted despite the forensic revolution is one of the real mysteries in American law enforcement. The backlog of DNA testing has certainly slowed down the process in many cases. Lab testing may have forced a “pause” in murder investigations, which causes delays that can dramatically reduce the odds of a homicide being solved.

Homicide detectives say the standards for charging someone are higher than they used to be. Prosecutors want police to deliver open-and-shut cases. Has that discouraged police from clearing cases they might have before?

We don’t have much guidance to give on this question. Haven’t had too many homicide detectives make this complaint, although we do know that many district attorneys have increased their standards following some embarrassing exonerations as a result of the Innocence Project and the DNA revolution.

Is there a jurisdiction that does homicide investigations really well and that has a good success rate? NPR’s story cites Richmond, Virginia as one example. Who else have you seen doing this well? What lessons can other jurisdictions learn from procedures there?

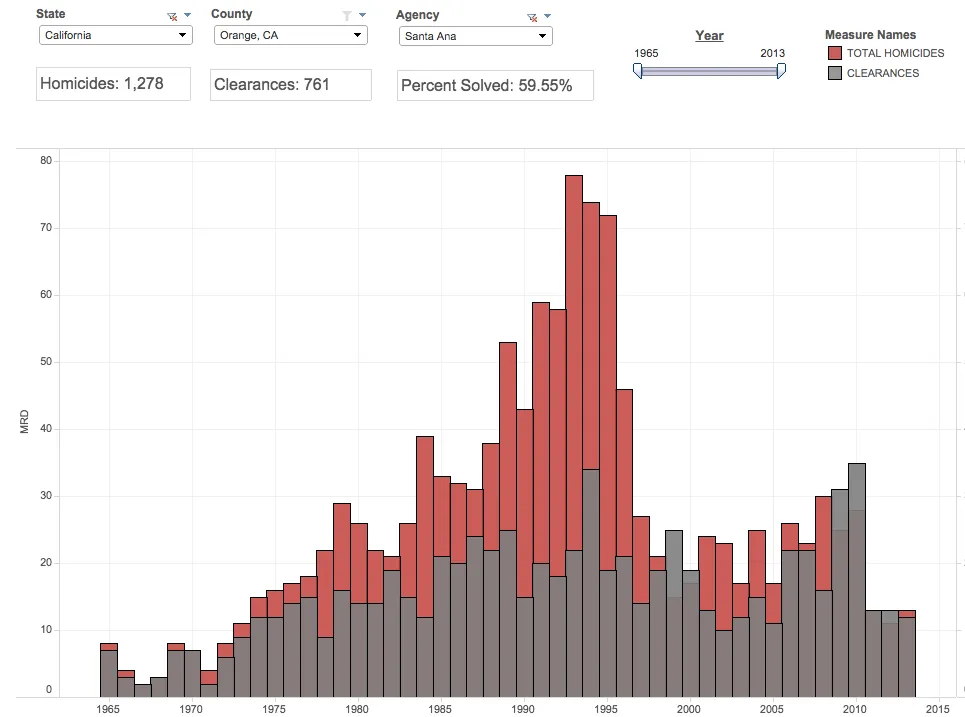

We can point out dozens of departments that have gone unheralded after making dramatic improvements in their homicide clearance rates. Police in Durham, N.C., have developed neighborhood canvass procedures in which local leaders, even members of the City Council, knock on doors to persuade reluctant witnesses to come forward. Police in Santa Ana, Calif., retooled their internal lab capabilities and developed effective anti-gang tactics.

Santa Ana in recent years is solving more murders than it reports as detectives begin tackling their cold case backlog. These departments should be celebrated by local citizens who take the time to look up the data to see how effective they are.

In a previous version of this article, the numbers cited for Canada’s homicide clearance rate were incorrect. In response to a note from a reader, this story has been updated with the correct figures.