From Nixon to Reagan to the first President Bush, Republican campaigns were run like campaigns for sheriff. Nixon ran against unprecedented lawlessness and promised law and order to the silent majority. Reagan remained consistent in his view that “the jungle is waiting to take over. The man with the badge holds it back.” And George H.W. Bush rode the menacing image of Willie Horton, the furloughed rapist, to victory over Michael Dukakis. Then, in 1992, Bill Clinton took time out from his chaotic comeback in New Hampshire to preside over the execution of Ricky Ray Rector, a mentally disabled man who had shot out most of his frontal lobe.

Clinton not only took the crime monkey off the back of the Democratic party, he also enacted draconian legislation that has been a key driver in making the United States by far the most heavily incarcerated society in the world: 2.2 million men and women behind bars, disproportionately African-American, Latino, addicted and mentally ill, at an estimated annual cost of $73 billion. Yet over the last quarter century, violent crime rates have been falling, dramatically.

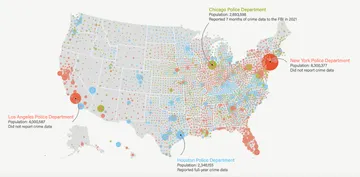

Of course, it can be argued that the decline is the product of mass incarceration, but a recent study by the Brennan Center shows that the effect of increased incarceration on crime rates since 1990 has been limited, and has been non-existent since 2000. Although the Times recently reported “a startling rise in murders after years of declines,” Bruce Frederick, analyzing the statistics for the Marshall Project, found that only 3 of 20 cities have a “statistically reliable increase” in homicide rates.

In an age of hemorrhaging costs and declining crime, fiscally responsible Republicans have begun to make common cause with Democrats to start to shrink the prison-industrial complex. The Brennan Center recently published a collection of essays entitled "Solutions: American Leaders Speak Out on Criminal Justice Reform." In his contribution, Rand Paul called for investigation of racial disparities in sentencing and argued against imprisonment for non-violent drug offenders, who make up the largest single group behind bars. Ted Cruz decried mandatory minimum sentences, which vests too much power in prosecutors. Marco Rubio declared there were too many federal crimes that were too poorly defined, and too poorly disclosed. Chris Christie, Rick Perry, Scott Walker and Mike Huckabee all called for compassion for drug offenders and showed interest in drug treatment as an alternative to incarceration.

Then along came Trump, blowing the old Republican dog whistle on race and crime. Ronald Reagan’s “jungle” was encroaching again, this time from the south. Mexicans are “bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists.” Doubling down when the statistics showed otherwise, Trump said “I don’t have a racist bone in my body,” but reiterated that Mexicans coming here “are, in many cases, criminals, drug dealers, rapists, etc.” His website section on issues does not address crime, or indeed any other issue, except one — immigration.

The conservative National Review sees the potential here for a Republican renaissance on fear of crime. In a recent paean to Nixonian nostalgia, “Revive Law and Order Conservatism,” Stephen Eide writes, “So long as the New York Times and anti-cop activist groups continue with their provocations, we can be reasonably confident that more violent unrest is to come. The spectacle of chaos descending on cities long dominated by Democrats obviously plays to the GOP’s advantage.”

He decries conservative attitudes on crime as “notably softer now than they have been in many decades.” Acknowledging that “New York City’s murders hit a 50-year low,” he observes, “there were still more than three times as many as in London, which has about the same population.” Surely that could have nothing to do with robust Second Amendment rights, another cornerstone of the Republican platform. Eide counsels Republicans that a key to victory in 2016 is to “emphasize that we still have a serious crime problem.”

Republican candidates are taking note. On Hot Air, a conservative web site, Scott Walker properly lamented a recent spate of tragic police shootings but blamed them on President Obama. “In the last six years under President Obama, we’ve seen a rise in anti-police rhetoric. Instead of hope and change, we’ve seen racial tensions worsen and a tendency to use law enforcement as a scapegoat.” And Chris Christie threw Bill de Blasio under the bus as well, “It’s the liberal policies in [New York] that have led to the lawlessness that’s been encouraged by the president of the United States,” he said. “And I’m telling you, people in this country are getting more and more fed up.”

Republicans are increasingly positioning the issue as a rift between Black Lives Matter and police unions, between Sanctuary Cities and thousand mile anti-rapist walls. The constructive discourse in recent months about the crushing costs of incarceration, the waste of mandatory minimum sentences, the twin crises of mental health and addiction in prison, the endless cost and delay in enforcing the death penalty has all but ended. In its place, Republicans are moving toward the traditional toxic brew of race, ethnicity, white middle class insecurity and panic about crime.

Get ready for the return of Willie Horton.

Eric Lewis is the chairman of Reprieve US, a human rights organization.

The original version of this story mistakenly referred to the man executed in Arkansas as Ricky Lee Rector. He was Ricky Ray Rector.