When police officers found the bodies of two children inside a hot pickup truck in Tulsa, Oklahoma, blame quickly fell on their father. Dustin Lee Dennis was supposed to be watching the 3- and 4-year old; instead, he slept the June afternoon away while they climbed into the truck, prosecutors said.

The children died June 13 from heat exhaustion as the temperature outside rose to 94 degrees. Tulsa County prosecutors charged Dennis with second-degree murder and felony child neglect.

But a landmark decision by the U.S. Supreme Court upended the case. The court ruled July 9 that, under treaties dating back two centuries, much of eastern Oklahoma is Indian Country. That means tribal law and federal law, apply there in criminal cases involving Native citizens—not state law.

The children were members of the Cherokee Nation. So the district attorney, Steve Kunzweiler, had to dismiss the case.

When he gave their mother the news, he recalled, “She just had this thousand-yard stare. And I didn’t have any better answer. I can’t do anything to help them anymore.” The mother, Cheyenne Trent, declined to comment.

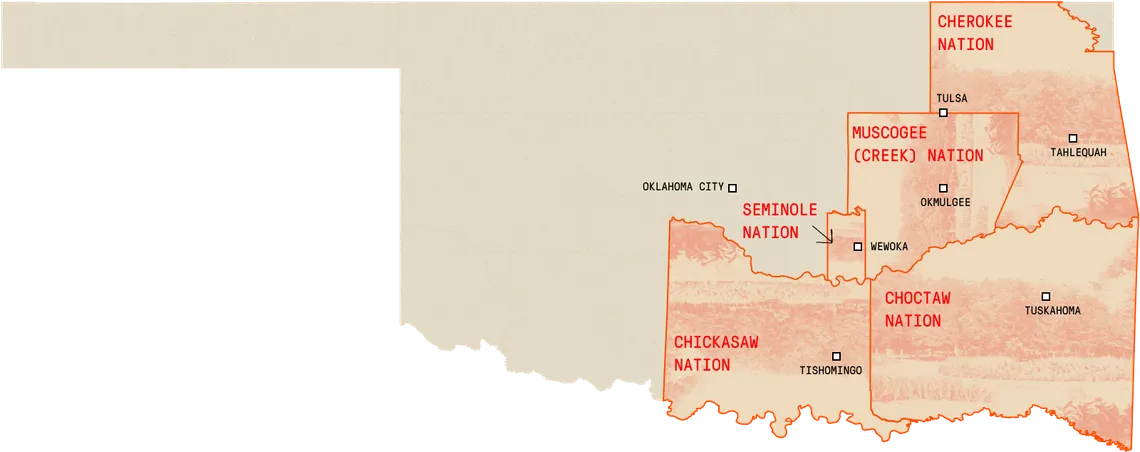

The Supreme Court ruling is a long-awaited triumph for the Five Tribes, which were forced from their homes and onto the Trail of Tears in the early 1800s by the U.S. government. Today, half a million tribal citizens live in dozens of Oklahoma counties covering more land than the state of South Carolina.

For tribal citizens, the ruling involves much more than the boundaries of criminal jurisdiction; it constitutes an important victory in the struggle to strengthen tribal sovereignty. Meanwhile, Indigenous plaintiffs are already using the Supreme Court’s decision to bolster legal cases for sovereign and tribal rights. A lawsuit filed in July by the Native American Rights Fund and several tribes builds off the decision to challenge President Donald Trump’s massive reduction of the Bears Ears National Monument in southern Utah.

But questions remain about what the decision means for the quality of justice in Indian Country, for Natives and non-Natives. An unknown number of tribal citizens who were convicted of felonies in state courts can now seek to be retried in U.S. District Court in Tulsa or Muskogee, Oklahoma. The case the Supreme Court ruled on, McGirt v. Oklahoma, involved the sexual abuse of a child.

It’s not entirely clear how prosecutions will work, because of tension between the state and the tribes over what is best for both public safety and tribal sovereignty. And there are questions about how federal prosecutors will handle what could be an influx of unfamiliar legal cases.

State officials are also worried that the court ruling could bring even more sweeping changes to Oklahoma. When Gov. Kevin Stitt created a new commission to examine the potential impact of the McGirt ruling, he did not include law enforcement officials or tribal leaders. Instead, he appointed several energy industry executives. A spokesperson for Stitt declined to elaborate on how the commission’s members were chosen.

Across the country, tribes and their citizens have been fighting—physically, legally, morally—to protect and increase their sovereign rights for generations; they see the Supreme Court’s decision as a major victory in that battle.

When it comes to the legal system, tribes ultimately want to regain their power to administer justice according to their own laws and traditions, said Sarah Deer, a legal scholar on criminal justice in Indian Country and a citizen of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation.

“So they can prosecute any crime, sentence whatever is appropriate for that community, they can develop unique ways to resolve disputes without punitive measures,” Deer said.

Even after the Supreme Court decision, tribal courts in Oklahoma and on reservations across Indian Country rarely have the authority to try felony cases and have very limited authority over people outside the tribe even in incidents that occur on tribal lands.

Until the Supreme Court ruling, most felonies in eastern Oklahoma, including cases involving tribal citizens, had been prosecuted in state courts by district attorneys.

Now, the U.S. attorney’s offices will have to handle serious crimes, including murder and assault, as their peers do in cases involving tribal reservations in more than a dozen states. While the federal prosecutor in Tulsa says his staff is willing to pick up these cases, critics note that the Justice Department has had a long history of documented lapses in handling cases in Indian Country. For example, in the past it has declined to prosecute almost half the violent crimes committed on reservations.

The Dennis case may be one of the first to test the new jurisdictional reality in Oklahoma. Shortly after Tulsa County dropped the charges against him, the U.S. attorney for the Northern District of Oklahoma announced that his office would prosecute Dennis for child neglect, taking the case before a federal grand jury within 30 days.

It’s an unusual crime for that office to try; the federal government generally devotes its prosecutorial resources to uncovering drug rings, human trafficking and multimillion-dollar financial crimes. There’s no federal statute on child neglect, just a law governing major crimes in Indian Country. Researchers at Syracuse University who track federal prosecutions found that in 2019, U.S. attorneys prosecuted only 20 cases nationwide under that law; the previous year, there were only five.

Trent Shores, the U.S. attorney for the Northern District of Oklahoma, acknowledges the decision has presented his office with challenges. His office has received 92 cases to handle in less than a month; his office only has 22 prosecutors and typically handles 15-20 indictments a month.

A citizen of the Choctaw Nation, Shores also happens to be the only Native American U.S. attorney, with a background of prosecuting cases in Indian Country. But now, his office is dispatching FBI agents to the scene of domestic violence complaints and figuring out what to do with juveniles who commit serious crimes in Indian Country. (His office is asking for help from Tulsa County’s juvenile prosecutors.)

“I’m having to triage cases as they come through the door,” Shores said. “I want people to remember that in the meantime, when they call 911, somebody’s gonna show up.”

Shores filed federal murder charges this week against a man who killed a Cherokee Nation citizen within the new boundaries of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation’s reservation.

BROKEN PROMISES

In 1834, Congress originally defined Indian Country—the legal designation for Native land—as “all land within the limits of any Indian reservation under the jurisdiction of the United States Government.” Thirty years later, the federal government forced tribes to break apart their communally held lands, and the eastern half of what would become Oklahoma was divided into individually owned allotments that were given to members of five tribes: The Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole and Muscogee (Creek).

In 1881, in what is now South Dakota, a chief of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe was murdered by a tribal member named Crow Dog. The tribe’s leaders, who relied heavily on a system of restorative justice, decided that Crow Dog’s family would make restitution to the victim’s family. The Supreme Court affirmed the tribe’s power to do so in Ex Parte Crow Dog.

In response, Congress passed a law known as the “Major Crimes Act,” which gave the federal courts jurisdiction over violent felonies involving tribal citizens, such as murder and kidnapping.

Around the same time, the federal government was also allowing White settlers to stake claims in Indian Territory. By 1907, when Oklahoma became a state, the settlers had taken most of the land.

“Oklahoma had been for decades treating that reservation as if it had been ‘disestablished’ basically with statehood,” said Lindsay Robertson, a professor at the University of Oklahoma College of Law. But in the McGirt ruling, the Supreme Court agreed that Congress never explicitly dissolved the Muscogee (Creek) Nation’s reservation.

In the eyes of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation attorney general’s office, the reservation has always existed. “That’s been our position since 1866,” then-Attorney General, Kevin Dellinger said in 2018, when the Supreme Court first accepted the Murphy case.

Most non-Native people don’t realize the tribes have prosecutors, courts and law enforcement, Dellinger said. “Our police force operates like any other police force in the county.”

Because of the Supreme Court ruling, the Muscogee (Creek) Nation Lighthorse Police Department, which employs nearly 60 officers, now has a jurisdiction that spans 11 counties. “Ideally, we’d hire 1,000,” said Deputy Chief Daniel Wind III.

Lighthorse officers patrol areas across those 11 counties, as well as the tribe’s government complex in Okmulgee, a city south of Tulsa, where they have worked in partnership with the city’s police department through a “cross-deputization” program. (The department has such agreements with 45 law enforcement agencies.).Partnerships and agreements between the state and tribes also exist for hunting and fishing licenses, water rights, tobacco and gas taxes and license plates.

Mike McBride III, a lawyer and former attorney general of the Seminole Nation, said the Supreme Court’s decision could ultimately restore the tribes’ ability to tailor their justice systems to their unique histories. Exercising that power is a key component of nationhood, he said.

“Almost all the tribes in Oklahoma and across the country have constitutions, and almost all of them reference courts or court powers,” McBride said. “Adjudicating and resolving disputes according to your own laws, customs and traditions—that’s a very important thing.”

CLEAVING OKLAHOMA IN HALF

In 2000, a jury convicted Patrick Murphy of murder for ambushing, killing and mutilating a romantic rival. While he was on death row, his lawyers argued that the state of Oklahoma never had jurisdiction over his case. Because he and the victim were both citizens of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, and the killing occurred within the boundaries of tribal land, only a federal jury could prosecute him. Lower courts rejected the claim, but in 2017 the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals agreed.

Meanwhile, a similar argument was making its way to the Supreme Court in the case of Jimcy McGirt. A jury in Wagoner County, southeast of Tulsa, had convicted him of the 1996 sexual assault of a 4-year-old Seminole girl and sentenced him to life—plus 1,000 years—in prison; it wasn’t his first conviction for sex crimes against a child.

McGirt spent years in an Oklahoma prison before filing a new claim to overturn his conviction: Because he is a citizen of the Seminole Nation and the crime happened in Indian Country, his case should have been prosecuted in federal court.

Lawyers for the state argued that rulings in favor of McGirt and Murphy would lead to anarchy for the court system and “open the floodgates to countless attacks on convictions.” Tribal lawyers and prosecutors called that claim ludicrous, noting that any prisoners in Oklahoma who successfully challenged their convictions would still be subject to re-prosecution in federal court.

The Supreme Court ruled in favor of both McGirt and Murphy. Both men remain in state prison in Oklahoma; their lawyers did not respond to requests for comment. They are likely to be retried in federal court, where last week, prosecutors filed criminal charges against both men.

Under federal law in Indian Country, tribes must opt-in to have the death penalty as a punishment option—none of the Five Tribes has.

Legal scholars argue that the Major Crimes Act helped drive over-incarceration of Indigenous people in the federal prison system. Native men are four times more likely to be incarcerated than their White counterparts, and that rate is six times higher for Native women, according to the National Council on Crime and Delinquency, a nonprofit social research organization.

Because of federal sentencing guidelines, people convicted in federal courts often receive much longer sentences than people convicted of similar crimes in state courts. Federal prisoners are often sent to prisons far from their homes, fraying their connections to their children and families.

“Kids are going years without seeing a parent when they have one in federal prison,” said Isabel Coronado, a member of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, who studies the effect of criminal justice policy on Native communities for Next100, a progressive think tank.

“I’m hoping with the big criminal justice discussion that’s been going on in Oklahoma that they’ll be looking to the prevention side instead of just sending people off to the federal side to serve time.”

Outside Oklahoma, Native men and women are frequently prosecuted in federal court for low-level drug crimes that occured on reservation land. That’s how Andrea Circle Bear, a pregnant mother of five and citizen of the Cheyenne Sioux River tribe, ended up in a federal prison outside Fort Worth, Texas, far from her family in South Dakota. She died after contracting COVID-19 in the federal prison system in April, shortly after giving birth to her youngest daughter.

Still, there are financial benefits to federal jurisdiction, said Sara Hill, attorney general for the Cherokee Nation. “You can see it all across eastern Oklahoma, the roads that are built, the bridges, the hospitals that are built. We’re pretty good at using federal money to raise all the ships in the harbor.”

Hill said existing partnerships between federal and tribal prosecutors provide a framework for a more adequate justice system for tribal citizens, though the changes will definitely require offices like hers to increase staff.

AGREEMENT IN PRINCIPLE?

After the Supreme Court verdict, Oklahoma officials announced that they had an “agreement in principle” with tribal leaders and the state’s delegates to Congress to share prosecutorial power, essentially returning the system to the way it operated before the ruling.

Mike Hunter, the attorney general for the state of Oklahoma, had told reporters that “this decision is not going to impact the mutual interest of public safety for both Indians and non-Indians in the state.”

But almost as soon as the agreement was announced, it fell apart.

Within hours, the Seminole Nation issued its own statement, saying that it “does not consent to being obligated to an agreement between the other four tribes and the state.” Pressure built on other tribal leaders.

“Now is the time to stand for sovereignty, not to give it away,” wrote Suzan Harjo, a prominent Cheyenne and Hidulgee Muscogee advocate for Indigneous rights, in an open letter to Muscogee (Creek) Nation Chief David Hill.

Chief Hill (who did not respond to interview requests), issued a statement shortly after the Seminole Tribe’s announcement, saying he no longer agreed with the “agreement in principle.” The other tribes pulled out as well.

Meanwhile, Kunzweiler, the district attorney for Tulsa County, is dealing with the new post-McGirt reality. His staff is going through every pending criminal case to look at where the crimes occurred and whether the accused or the victim is a tribal citizen, he said. His office prosecuted nearly 6,000 felonies last year.

The U.S. attorney’s office announced that it would prosecute Dennis and a non-Indian man who allegedly killed his Cherokee girlfriend. But Kunzweiler said he wonders how many more cases federal prosecutors can handle. Are they going to start prosecuting felony drunk-driving charges?

“Mostly, I’m worried about victims,” he said. “We’ll sort out the jurisdictional issues, but I don’t want to traumatize them anymore than they already have been.”

Hill, the Cherokee Nation attorney general, said there are day-to-day issues to be worked out, but the tribes already work regularly with federal prosecutors.

“There’s always people who want to see this as ‘We’re just going to open the jails, and Indians don’t have to follow the law anymore,’” she said. “That’s just not the case.”

Graham Lee Brewer is an associate editor at High Country News and a member of the Cherokee Nation.

Cary Aspinwall is a Dallas-based staff writer for The Marshall Project. Previously, she was an investigative reporter at The Dallas Morning News, where she reported on the impact of pre-trial incarceration and money bail on women and children in Texas and deaths in police custody involving excessive force and medical negligence. She won the Gerald Loeb Award for reporting on a Texas company's history of deadly natural gas explosions and is a past Pulitzer finalist for her work exposing flaws in Oklahoma's execution process.

Correction: Mike McBride III is the former attorney general of the Seminole Nation. An earlier version of this article misstated his first name.