This is The Marshall Project’s Closing Argument newsletter, a weekly deep dive into a key criminal justice issue. Want this delivered to your inbox? Sign up for future newsletters.

This July, a man in Utah set his home on fire, killing himself, his 33-year-old partner, Jaimar Bravo Gil, and their children, police say. The family had moved to the U.S. from Venezuela, and Bravo Gil’s relatives said her partner had a history of violence but she had kept silent about most of the abuse for fear of being deported. She was not alone. At least two other women killed by their intimate partners this summer reportedly did not seek police help because they also feared deportation.

A growing chorus of attorneys, advocates and members of law enforcement are warning that the terror that has taken hold in immigrant communities is causing some people to remain in abusive relationships rather than risk deportation and separation from their families. While undocumented victims have always faced barriers in escaping abuse, experts say Trump administration policies have left them much more vulnerable.

The Department of Homeland Security did not respond to a request for comment.

Here are six changes impacting immigrant victims of domestic violence:

In January, DHS rolled back protections that kept immigration agents from entering “sensitive locations,” including domestic violence shelters and hospitals. DHS also began allowing enforcement at courthouses.

These changes have caused some domestic violence victims to think twice before seeking medical help, moving into a shelter, or seeking an order of protection, experts say.

There have been reports from across the country of immigration officers arresting people at courthouses, sometimes violently. A recent survey of more than 170 attorneys and advocates for immigrant survivors of domestic and sexual violence found that 70% said their clients had concerns about going to court for a matter related to their abuser.

Some jurisdictions are pushing back. In October, the top judge in Cook County, Illinois, which includes Chicago, issued a local order barring civil ICE arrests in and around courthouses. Weeks later, Illinois lawmakers passed legislation barring civil ICE arrests in all state courthouses.

ICE raids have also had an impact on domestic violence shelters in Los Angeles and elsewhere. One advocate shared a story of a client who waited two days after an assault to go to the hospital. She only went after her attorney told her it was safe, and was found to have a broken nose and eye socket, according to a press release from the Alliance for Immigrant Survivors.

The Laken Riley Act requires detaining undocumented immigrants accused of certain crimes, even petty ones. Advocates say this will wrongfully ensnare domestic violence victims.

It is common for the victim to be arrested along with the abuser, or for abusers to call the police on undocumented victims as a form of control, experts say. And sometimes, victims commit crimes to survive, like shoplifting diapers or food for their children.

Under prior laws, an immigrant could discuss their abuse with a criminal court judge and argue for bond while the case is pending. Under the Laken Riley Act, passed by Congress in January, survivors have to make their case from inside the immigration detention system, and could be kept in custody throughout their case, even if the criminal allegations against them are later dropped.

Local police are often cooperating with ICE, and new funding incentivizes such partnerships.

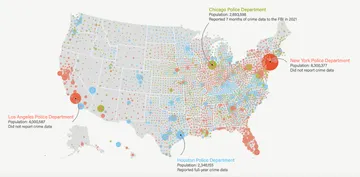

Under the Trump administration, DHS has been aggressively pushing local police to make immigration arrests and share information on possible targets through a program known as 287(g). The federal government is now offering to reimburse the pay of local officers. The federal government lists over 1,000 agreements with law enforcement across 40 states.

“For survivors, this raises a critical question,” said Cecelia Levin, advocacy coordinator for the Alliance for Immigrant Survivors. “If an officer arrives at the door, what are they there to do? Are [officers] there to offer protection and help, or are they there to conduct an enforcement action?”

In Houston, the police department’s calls to ICE have increased more than 1,000% this year, the Houston Chronicle recently reported. Most referrals were related to traffic stops. This June, a Houston officer warned a woman reporting her abuser that the police contacted ICE and advised her not to file a report in person or risk being deported, she told the newspaper.

Domestic violence organizations, including shelters and legal aid, are facing financial turbulence as conditions for federal grants change repeatedly.

The Trump administration has issued a dizzying array of new policies that specifically impact immigrant victims of domestic violence. The federal Office on Violence Against Women set new conditions for its funding, requiring applicants to certify that they are not promoting gender ideology, DEI, or prioritizing “illegal aliens” over citizens. A group of state-level coalitions for survivors sued, and a federal judge temporarily blocked the new funding restrictions.

The administration also tried to use Victims of Crime Act grants — which fund compensation and assistance programs — to compel states to comply with federal immigration demands. The administration later backed off of this threat.

Then, in August, the administration said it would bar states from providing services to crime victims who “cannot immediately prove their immigration status” — a move being challenged in federal court by more than 20 state attorneys general.

While the lawsuits against these policies have had some wins, cuts are already happening. In Tennessee, for example, the state’s office that decides how to spend federal crime victim dollars ended immigrant legal aid grants this past June.

Safety nets for immigrants have been cut, making people more vulnerable.

This summer, the Trump administration announced that unauthorized immigrants would be barred from receiving certain social services, including Head Start, which has long supported families with education and health care for children. In September a federal judge blocked the policy change.

Cuts to assistance were also part of the Big Beautiful Bill, which made certain lawful immigrants, including survivors of domestic violence and human trafficking, ineligible for SNAP food aid, Medicaid, and health care tax subsidies. As a result, an estimated 90,000 people will lose SNAP benefits in a typical month, according to the Congressional Budget Office. These benefits have never been available to people who are undocumented.

Nearly 80% of advocates polled in a 2017 survey by the National Resource Center on Domestic Violence reported that “most domestic violence victims rely on SNAP to help address their basic needs and to establish safety and stability.”

Losing food benefits, together with potential cuts to other support services, creates a heightened level of vulnerability for immigrants, making them more susceptible to ongoing abuse, experts say.

Some worry that the administration’s next target is protective visas.

Abusers can exploit people’s immigration fears, and the vulnerability of undocumented women is part of why Congress passed the Violence Against Women Act in 1994. The law allows survivors to apply for permanent residence without the abuser’s involvement. The visas, U visas for victims of domestic violence and other serious crimes, and T visas for victims of human trafficking, require that they cooperate in the arrest and prosecutions of those who harmed them.

Police often embraced the tool, said Zain Lakhani, migrant rights and justice director at the Women’s Refugee Commission. “It enables law enforcement to be able to conduct investigations. It keeps the witnesses around, and it makes it safe for people to report crime.”

The special visa process has, for years, been plagued by lengthy wait times, which have grown to over a decade, according to The 19th. Applicants are supposed to receive protection from deportation while their application is awaiting a final decision, yet over the past year, women have been forced out of the country while waiting on pending T or U visas. A lawsuit seeking to halt those deportations is pending, and legislation to do the same has been introduced in Congress.

Project 2025 called for the total elimination of both visas, concluding that “victimization should not be a basis for an immigration benefit.” The 19th reported that access to these visas is already being restricted. About 3 in 5 applicants for these visas are immigrant women.

So what safe avenues still exist for immigrants who need to escape from abuse?

Advocates for survivors told The Marshall Project there is still help available. Local and national domestic violence hotlines are confidential, and they can help people understand what their options are and how to make a safety plan. Shelters take the privacy and safety of people in their care seriously and immigration agents would need a warrant signed by a judge to enter without permission and cannot rely on abuser-provided information to find people. The rules surrounding certain protections, like special visas, are still the law. Legal aid for immigrants is still available in many places, and attorney client privilege is legally protected regardless of immigration status.

And in many jurisdictions, advocates and attorneys are providing their services virtually, and using remote court options, said Casey Swegman, director of public policy at the Tahirih Justice Center, which serves immigrant survivors of gender-based violence.

“We are ready to serve folks, and no survivor should feel like there isn’t help out there,” Swegman said.

If you or someone you know needs help, please call the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 800.799.SAFE (7233) or the Tahirih Justice Center at 1 (866) 575-0071.