Subscribe to “Smoke Screen: Just Say You’re Sorry.”

Texas Ranger James Holland is one of the most celebrated homicide detectives of the last decade. The Los Angeles Times called him a “serial killer whisperer,” after he helped convince California prisoner Sam Little to confess to more than 90 murders. Following Holland’s work, the FBI declared Little, who drew pictures of many of his victims, the “most prolific serial killer in U.S. history.”

But as Holland’s star was rising, one of his past cases was getting new scrutiny.

By 2019, prisoner Larry Driskill was writing letters to the Innocence Project of Texas, arguing that he’d been railroaded by Holland into making a false confession to the murder of Bobbie Sue Hill. He found a receptive audience in law student Ashley Fletcher, who was screening letters for the organization. Fletcher soon joined two of the project’s lawyers, Mike Ware and Jessi Freud, as they went to visit Driskill in prison.

As Ware and Freud began working to prove Driskill’s innocence, they were bolstered by journalists who were writing about some of the specific tools used in the case. At the Dallas Morning News, Lauren McGaughy published a major investigation in 2020 about the risks of forensic hypnosis. At ProPublica and the New York Times Magazine, Pamela Colloff dissected the role of jailhouse informants in sending innocent people to prison.

Episode 5 of “Smoke Screen: Just Say You’re Sorry” is called “The Serial Killer Whisperer.” It details Holland’s work on the Little case, as well as the growing skepticism in Texas around forensic hypnosis and jailhouse informants.

Listen to new episodes each Monday, through the player at the top of this page, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Go deeper:

Transcript:

Before we start, a warning that this episode contains descriptions of violence. Please listen with care.

This time on “Just Say You’re Sorry”:

Jessi Freud, lawyer for Larry Driskill: It starts with [law student] Ashley [Fletcher] frantically telling me, and Mike, “Holy shit, you're not gonna believe this!”

Mike Ware, lawyer for Larry Driskill: That whole timeline is so shaky. Nobody can say how long she had been dead.

Jillian Lauren, journalist who knew Texas Ranger James Holland: He’s just sort of a Greek tragedy, you know, cause like you want that person to be a hero and he, he’s just got this hubris.

We’re going to start this episode far from Texas, in another state that also has a strong sense of identity and mythology: California. We’re just an hour’s drive north of Hollywood, but you wouldn’t know it, because prisons tend to look the same wherever they are. A journalist named Jillian Lauren is entering one for the first time.

Jillian Lauren: The big gate closes behind you. You know, they gave me a whole lot of shit at the metal detector because of my nose ring. I had to, like, pry my nose ring out — a bloody nose. And my underwire. I had to chew my underwire out of my bra. It was a very feral kind of first introduction to a men's maximum security prison.

After all that, Jillian enters a visitation room to interview a prisoner.

Jillian Lauren: So he's an old man in a wheelchair. I was a foot from his face. He did something that is very common with narcissists. He talks very, very quietly. Very quietly.

His name is Samuel Little. He’s 78 years old and soft-spoken. He’s been convicted of three murders. But, a detective has told Jillian, We think he killed other people, too. Nothing’s been proven. So Jillian’s just a reporter with a good lead.

She knows she needs him to trust her. Somehow, she figures out how to make him laugh. Turns out they both like boxing. And then…

Jillian Lauren: Sam started confessing to me. It was quite a remarkable moment that I guess I didn't think was going to happen. It was one of these things I jumped into because it sounded really exciting. And also I felt politically, and, like, emotionally motivated.

He reveals that he killed numerous women. A lot of them were sex workers. Jillian had done sex work herself and she felt lucky to have survived. So she feels a sense of mission to these women who the police, and society, seemed to have ignored.

She spends hours with Little every weekend. He calls her at home.

Jillian Lauren: I made myself essential to him. I mean, I gave up my soul. I talked to him every day.

Over more than a month, he confesses to roughly two dozen murders spanning decades. There’s a lot of detail. He tells her what he remembers playing on the radio, or about a particular smell in the air. He can draw pictures of many of his victims’ faces.

But he doesn’t know their names and Jillian doesn’t have the resources to match all of these claims to known cases and see if they’re true.

And then she finds out she’s not the only person visiting this elderly prisoner.

Jillian Lauren: And then he starts going, “Oh yeah, there's a space cowboy. There's a space cowboy named Jimmy, my friend Jimmy. You and Jimmy, you're my only friends.” And I am like, “Oh shit.”

Texas Ranger James Holland doesn’t go by the name “Jimmy,” to most people, but he does with Samuel Little, who he calls “Sammy” in return. Holland has also been trying to get Little to confess to long-ago murders, and this is the case that will send his career into the stratosphere.

From Somethin’ Else, The Marshall Project, and Sony Music Entertainment, I’m Maurice Chammah, and this is “Smoke Screen: Just Say You’re Sorry.”

Episode 5: The Serial Killer Whisperer.

Last time, we heard how Larry Driskill, under the weight of his own confession — and the news that there was a jailhouse informant ready to testify against him — pleaded no contest to the murder of Bobbie Sue Hill. He was sentenced to 15 years in prison.

But he is still protesting his innocence. Desperate for help, he writes a letter to the Innocence Project of Texas, and waits, wondering if anyone will ever read it.

Ashley Fletcher: The letter was about two pages long, and it's written in very nice handwriting. I do remember noting that.

That letter lands on the desk of a young law student. Her name is Ashley Fletcher.

Ashley Fletcher: Ever since I was a little girl, I thought that I wanted to be a lawyer. It probably started with watching “Legally Blonde.”

By 2019, she’s at the Texas A&M University School of Law, in Fort Worth, and choosing what to focus on.

Ashley Fletcher: I thought that one would be really interesting and have a good impact on somebody's life. So I signed up to take the Innocence Project clinic.

This is common at law schools. Innocence Projects get a deluge of letters from prisoners. So they run special classes for the students to help them find the cases where they might actually be able to help, and Ashley gets assigned the letter from Larry Driskill.

Ashley Fletcher: “Dear Sir, I am actually innocent of this charge, first-degree murder. This case is the first time I’m…”

In the letter, Driskill outlines the key reasons he thinks a judge might take a second look at his conviction.

Ashley Fletcher, reading Driskill’s letter: “… wish the Texas Ranger would have relented in his attack on me when I asked if I needed an attorney…His interrogation lasted three hours the first day, with only one bathroom break and one cup of water for the duration. I did not fit the description. I appreciate your earliest response. Sincerely, Larry Driskill.”

Ashley is pretty new to law, but she knows these letters tend to sound similar, and that some of the authors might not be innocent at all — just desperate. But this letter sticks out, in part because it has a notable addition: a big stack of transcripts from the interrogation. Ashley takes all of it home.

Ashley Fletcher: I read them probably all through the night. I had this big ottoman and I was like, kind of hunched over to the couch, just reading this binder where I had all the transcripts printed out, and highlighting the crazy quotes that I thought were, you know, the most shocking things that Ranger Holland said.

What shocks Ashley the most is the way that, as she sees it, Holland uses seemingly innocuous parts of Driskill’s personal history to his own advantage.

Ashley Fletcher: Which for Driskill was religion and the fact that he was a vet. He served our country and was taught to trust authority. And so he was more vulnerable to the tactics that Holland used. And I think Holland knew that.

So she goes to Mike Ware and Jessi Freud, who are teaching the class. You heard from Mike in Episode 1; he runs the Innocence Project of Texas. Jessi is a criminal defense lawyer who works in Waco, but she’s also just like Ashley, only a few years ahead. She started working on wrongful conviction cases as a law student herself.

Jessi Freud: It starts with Ashley frantically telling me, and Mike, “Holy shit, you're not gonna believe this.” Just the urgency in her voice when she told us this, and it really just really took over our class…She was like, “This isn't right.”

Mike Ware: I mean, she was almost traumatized, I think, by what she was seeing going on. You know, the more I listened to her, I thought, ‘You know, this is a reasonable, rational reaction to what we're reading about here.’

Jessi Freud: Once we look at it and see kind of the red flags that Ashley saw, the statements were kind of oddly characterized as confessional in nature. When I think if you listen closely again over and over, Larry immediately recants in a way, if you wanna call it that, by saying, “But if I did this, I don't remember.”

Mike Ware: To me, if the Texas Rangers are involved, there’s a red flag.

Mike was a defense lawyer in the 1980s, during what was maybe the most embarrassing debacle involving the Rangers in recent history: the case of Henry Lee Lucas. Lucas became famous as America’s most prolific serial killer. He said he’d killed hundreds of people. But it turned out he was lying, probably for attention. Lucas even said he’d driven to Japan to kill someone.

Unnamed news anchor: Lucas now claims it was law officers themselves that gave him the tools necessary to make up all of those some 600 bogus confessions.

Unnamed news anchor: The task force. The conviction. The whole three ring circus had been based on Henry's evil imagination.

The Rangers claimed they were just facilitating interviews by other cops, but it was a huge blow to their reputation. A big waste of time and money. And worse: victims’ families had been given answers, only to have them ripped away again.

It’s not a chapter the Rangers like to remember, but it’s one that sticks out to people like Mike. And it makes him a little skeptical of the whole Ranger mythology.

Mike Ware: Through my experience, it seems like they always come in and just kind of screw things up.

So Mike and Jessi decide to go deeper. They plan a visit to Larry Driskill. And they invite Ashley to join them.

Ashley Fletcher: I was very excited to go and that something was actually happening on the case, and that this was actually going to go somewhere, that finally we were gonna listen to somebody whose case was so crazy. Somebody had finally looked at it. But I don't think it was as exciting once I got there, as I thought it was going to be. It was becoming more real.

Driskill doesn't seem especially excited to see them. He comes off to Ashley as maybe a little suspicious of them.

Ashley Fletcher: How I left was, like, ‘OK, we've got a lot more proving ourselves to do. He doesn't trust us yet.’ We weren't just gonna walk in there and save the day, you know, that was not gonna happen.

Getting an Innocence Project to take your case is a massive achievement, but it’s far from a get-out-of-jail free card. In reality, once you’ve been convicted, you’re always facing an uphill battle to get free. Prisoners have very few opportunities to fight their case in court.

But the Innocence Project of Texas team comes away from the meeting ready to go all in. They start by driving to the key locations in the case, including East Lancaster Street, where Bobbie Sue Hill was abducted.

Mike Ware: We went out to the scene and looked around the scene of where she supposedly got picked up. We looked at the scene where the body was found.

They’re in a similar position to James Holland and other detectives who tackled this case, trying to make headway in a part of Fort Worth where nobody sticks around for long.

Mike Ware: We were just kind of chasing a ghost out there.

They do, however, notice some issues with the original timeline of the murder.

Mike Ware: That whole timeline is so shaky because everybody's so indefinite. Nobody can say how long she had been dead.

They actually find one of Bobbie Sue Hill’s aunts. This woman had told police that she saw Hill alive, after the official date she was abducted.

Could that be true? Maybe. As we’ve discussed, memories are often hazy and incomplete and contradictory.

So then they look for physical evidence from the case. It turns out there was some — a cigarette butt found by Hill’s body was tested for DNA and led to a suspect. This was not Larry Driskill. This was one of the dead ends before Driskill was brought in. But perhaps the DNA holds more answers.

Jessi Freud: One of the easiest ways to show that somebody is actually innocent is to show that their biological material, their DNA, is not where it should be, if they were the true perpetrator of this. And so some of the items that we looked into testing, and are in the process of testing, [are] the duct tape from the bag that was secured over Bobbie's body. I believe we've also asked to have tested a number of samples from her sexual assault kit.

Maurice: And, and none of this stuff was tested way back?

Jessi Freud: None of this stuff was tested.

Maurice: Why?

Jessi Freud: Because you had a confession. You don't need DNA when you have a confession.

Maurice: That is wild to me.

In Holland’s own report he does say they’ve sent that evidence for testing, but I couldn’t find anything about the results. Jessi thinks that because of the confession, the order was either canceled or not added to the files.

So now, Mike and Jessi go to the Parker County District Attorney, who prosecuted the case, and ask: Can we run new DNA tests? The DA agrees. Prosecutors don’t always do that without a fight, so this is a success in and of itself.

Mike Ware: Well, they said, “OK, but you know, you're gonna pay for it.” And we said, “Yeah, we're gonna pay for it.”

I reached out to the DA Jeff Swain about the DNA testing. He responded that nearly all of the evidence had already been tested for DNA, but because the body was found in running water, there was never really a chance of recovering much to begin with.

So for the DA, all the necessary work was done years ago, and none of this new testing is likely to move the needle, while for Mike and Jessi, these tests still represent Driskill’s best chance of freedom. Only time will tell.

But there are other things the Innocence Project of Texas can do. Like tell me about the case.

Mike Ware: The more light we could shine on this case, the better. Someone with their own investigative perspective could help. We need to do whatever we can to sort of shake this loose because if the system just follows its normal course, nothing is ever going to happen on the case.

So that’s why Mike tipped me off to Driskill’s story. He knew I might follow different threads than would occur to his own team.

But he also told me I wouldn’t be the only journalist interested in James Holland.

While Mike was starting to look into the case, he saw a piece published in the Los Angeles Times. It was about Holland. The newspaper called him a “serial killer whisperer.”

Mike Ware: There's this article about Ranger Holland and his miraculous solving of a hundred cases or so from this one guy named Little.

So it's not a coincidence that he's the same guy in this case, you know? He is obviously in the confession business.

So while Larry Driskill is sitting in prison, Holland’s star is rising. And that’s thanks to another man, the prisoner in California named Samuel Little. Holland has worked his magic on this hardened criminal. Little is now confessing his way towards that title that we just can’t seem to let go of: America’s most prolific serial killer.

While Larry Driskill’s life is standing still, waiting in prison writing his letters to the Innocence Project of Texas, Texas Ranger James Holland, is nonstop. A few months after interrogating Driskill, he gets a confession from Christopher Ax, who we met in the last episode.

Then Holland begins an incredible professional run. Later that year, 2015, another guy is convicted after having confessed to Holland. It was a murder committed in 1968. Prosecutors say it's one of the longest gaps between crime and conviction in American history. The next year, Holland convinces a serial killer named William Lewis Reece to confess to multiple murders but also to tell him where some of the bodies are buried. I talked to the mother of one of these victims. She had waited nearly 20 years for answers. She called Holland her “hero.”

But even the Reece case is small compared with Holland’s next one. In 2017, he’s at a conference. He’s teaching interrogation techniques. A detective tells him about Samuel Little. Remember Little is in prison, in California, for several murders, but he is suspected of many more. Detectives are having trouble getting him to talk. Holland learns of some potential Texas victims that justify going to California to meet Little.

And this is how he meets the journalist Jillian Lauren.

Jillian Lauren: I thought it was wild. I really thought he was kind of a cowboy. I mean whether or not he was raised wearing those boots, I'm pretty sure he wrestled and killed whatever they made them out of.

As we heard earlier, Jillian is also interviewing Sam Little, and for the same reason: to get him to confess.

Her own life story couldn’t be more different than Holland’s. Before she was a journalist, in the early 1990s, Jillian was a sex worker. But not on the streets. She was paid as a kind of escort for the Prince of Brunei. She wrote a memoir about it.

An irrelevant fact that I can’t not mention here is that she’s now married to Scott Shriner. He’s the bass player for the band Weezer. She does radiate rock ’n roll glamor. Picture piercings, tattoos, hoop earrings.

As different as she is from James Holland, they share this rare experience of interviewing the same difficult-to-crack serial killer. She sees up close Holland’s biggest career success, his star turn, and the reason that, for so many people, he’s such a hero. Remember, some people think Samuel Little got away with his crimes because nobody cared about his victims.

Jillian Lauren: You know, I was sort of starry-eyed for the American hero, the cowboy, and also like, here's my white knight, right? He's fighting for marginalized populations of women who were ignored. And that's really… my heart.

When Holland first learns that she’s on his turf, he calls her.

Jillian Lauren: I got this Texas call. And so I sat down on my front steps and I took the call and it was Jim and he said, “I heard you've been talking to my boy Sammy.”

So she agrees to help him. She shares what she’s learned from the serial killer. Holland is trying to connect these various claims to real cases, to see if they match any unsolved murders floating around in old police department files. Samuel Little seems to have such a great memory of his horrible acts, but is any of this stuff true?

Some time later Jillian and her husband are at a movie premiere. She told me his band Weezer did some of the music. So I guess the Weezer thing was relevant after all.

Jillian Lauren: Scott and I went to the opening of a movie that his music goes in. Oh, it was “Cars 2.” Yeah, it was “Cars 2.”

A quick shout out to our fact checker Natsumi Ajisaka, who told me, “It wasn’t Cars 2.” That movie is far too old for this to make sense. I told Jillian this and she said, “Oops. It could have been ‘Frozen 2,’ which also has a Weezer song. Or maybe it was the Grammys.” To be honest, It was kind of a relief to talk about a memory error with such low stakes. And really the lesson here is: Jillian’s on a lot of red carpets.

So anyway, here’s her memory:

Jillian Lauren: And it was whack, like, ‘That's a lot of celebrities.’ It was a lot of [camera] flashes. And I had our little kid on my hip, and I get this call from Texas, and I went and hid behind a column, and it was Jim. And he said to me, “We found her.” He said, “We found her.”

They had successfully linked Little’s claims up with a cold case of a woman, Agatha White Buffalo, who had been found dead outside a tannery in 1973. The clues Little had been giving out, including the strange smell of the tannery, helped connect the dots. The family was getting an answer after all this time.

Jillian Lauren: I just remember him saying, “We got her.” And I was like, “Really? You got her?” And he was like, “Yeah, Jillian, we got her.” And I think that was probably my best moment I ever had with Jim, and so surreal with the surroundings, and memorable.

I also imagine that moment from Holland’s perspective. He’s calling a glamorous journalist at some Hollywood event. He’s come a long way from dingy interrogation rooms in small Texas towns. I wish I’d been able to witness this relationship between the Ranger and the journalist. On the one hand, she told me he’d get angry at her, telling her to “stay out of his way.”

Jillian Lauren: James Holland and I yelled at each other. I have never had a professional relationship like that. Jim was probably the most challenging and interesting professional relationship of my life.

But you can also hear the affection in her voice. She mentioned that he would never say the words “marijuana” or “weed.”

Jillian Lauren: It was always, like, “grass” or something. He talks like he's a fed at Woodstock, you know.

“A fed at Woodstock.” I love that phrase. She learns that he didn’t grow up in Texas, so she teases him about the whole cowboy thing.

Jillian Lauren: He told me that he grew up outside of Chicago. So he really, like, wore this cowboy mythology with a choice.

This version of James Holland sounds very different from the one I’d encountered in the Driskill and Ax cases. Those guys were free, living their lives, so Holland had to somehow convince them to confess even though it might put them in prison. But Samuel Little was already in prison. So Holland’s style is less about pressure and more about persuasion. They eat pizza and drink milkshakes. He massages Little’s ego, giving him a feeling of power and control, even suggesting he could move him to a nicer lockup, and in style.

Jillian Lauren: He was, like, “I can get you out of here, get you on a fancy plane. You're totally in control of this whole thing. You are the captain of the ship. I'm very impressed by you. How can you let this work you've done go unnoticed, go unseen?” Holland will do anything. There's something compelling about it and something just really scary. He is a very, very smart man, and an incredibly fast critical thinker.

This is from conversations Jillian had with Holland, when they compared their interviewing techniques.

Jillian Lauren: In the confessions of Sammy and Jimmy, you know, that report was painful for me, as a woman, but also I had respect for it.

Jillian says that Holland would sometimes appeal to Little’s misogyny, sort of get on his level and say terrible things about women too.

Jillian Lauren: He is like, “OK, so tell me, who's the fattest bitch you ever killed? Come on… and then you did what to her? … Ah, man, I hate that, you know, they fuck with you and…”

Maurice: Into this almost like gross, like bro-ey style?

Jillian Lauren: It was so “bro.” I said, “What do you think the families are gonna say?” And he said, “I think they want the black-and-white son-of-a-bitch who is going to solve the murder of their family member. And I think if they want somebody to sit with them and pray with them and cry with them, they can find someone else, I'm gonna go solve this case.

This actually reminded me of a moment in the Driskill case, when Holland says demeaning things about Bobbie Sue Hill. Maybe with certain killers, that’s what you’ve got to do, perform this whole callous act. Perhaps that actually is a service to the victim’s families. And Holland’s methods were clearly effective. According to the FBI, Sam Little confessed to 93 murders between 1970 and 2005. They’ve confirmed at least 50 of them, rendering him, to quote the FBI, the “most prolific serial killer in U.S. history.”

Unnamed news anchor: Over the course of 700 hours of interviews, while in prison for murdering three women, Little confessed to Texas Ranger James Holland that he killed many more.

James Holland: What city did you kill the most in?

Sam Little: Miami and Los Angeles.

James Holland: And how many did you kill in Los Angeles?

Sam Little: Los Angeles? Approximately 20.

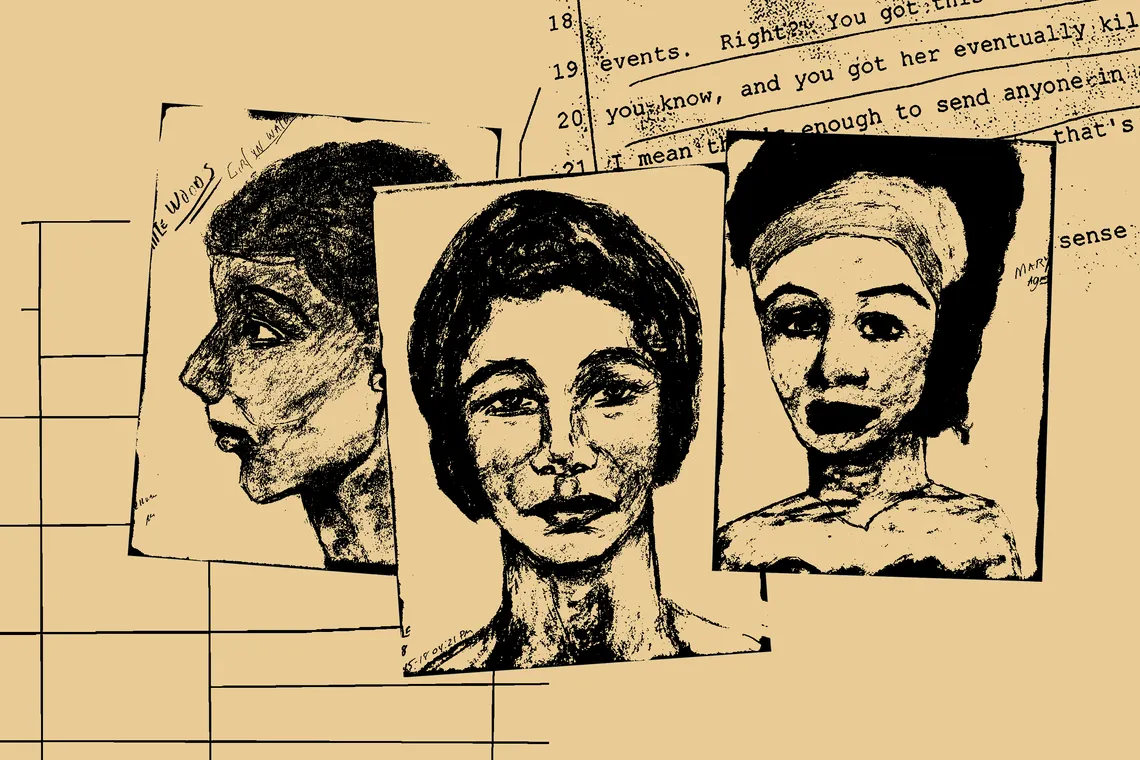

So the Los Angeles Times dubs Holland the “serial killer whisperer” and runs this photo of him in his office, surrounded by Sam Little’s drawings of women. Holland does an interview with “60 Minutes” on CBS.

CBS interviewer: Wow, these are all of his drawings?

James Holland: These are all his. The first thing I picked up on is how wicked smart he was.

Interviewer: Smart?

James Holland: Oh yeah, like a genius.

But of course, a certain set of Texans hear about all this and immediately think of that old con artist Henry Lee Lucas. “Most prolific serial killer in history?” Haven’t we seen this movie before?

Jillian Lauren: Jim was very careful to not repeat that. We spoke about it specifically. So do I think every single one of the confessions is exactly true? No, but I think Sam did his best for most of them.

Nobody has proven that Sam Little lied or that James Holland or Jillian Lauren were in any way duped. Little died in December 2020, so any further truths won’t come from him.

Of course, as a good journalist, Jillian Lauren wanted to know why I was looking into James Holland. I told her all about the Larry Driskill case. I was curious to hear what she made of the claim that Holland had elicited a false confession.

Jillian Lauren: From what I know of him, I don't believe Jim would intentionally coerce a confession.

This lines up with the impression I get. Nothing I've seen or read suggests Holland at any point thought he might have an innocent man. But Jillian does believe he could have gotten it wrong.

Jillian Lauren: It's so sad for me to say, because, you know, I sort of had the same starry eyes about him that everyone did. He's just sort of a Greek tragedy, you know. You want that person to be a hero. And then he's just got this hubris. He’s an Icarus. It’s thrilling to watch, but then you're like, “Ah, you're a little close to the sun there, buddy.”

I think she knows I’m going to find that description of Holland compelling. We live in the age of the anti-hero. We all like to hear about larger-than-life people whose flaws are as interesting as their accomplishments.

But it can also sort of blind you, because nobody operates in a vacuum.

To take just the example of Samuel Little, there were all these other departments working on those cases. When you zoom out further, you see how people are the product of their environments. Holland spent his career at the Texas Department of Public Safety, where he had bosses, he had trainings, and he was given certain tools. He didn’t invent the Reid Technique or the idea of buttering up a serial killer. Throughout his cases, as far as we can tell, he followed the rules. But other people wrote the rules.

And by 2021, with the Innocence Project of Texas working for Larry Driskill, some of these rules were starting to be questioned. A few state lawmakers, across the country, were beginning to talk about a ban on lying during interrogations. A lot of police departments were turning away from the Reid Technique.

And in Texas, there was a movement to ban one of the Rangers’ major tools. It’s one Holland relied on to identify Driskill as a suspect in the first place: forensic hypnosis.

As I go deeper and deeper into the Driskill case there are times when I feel stuck. The analysis from the Innocence Project of Texas is compelling. They see a wrongful conviction based on a false confession, obtained by an arrogant Ranger with tunnel vision. And we know about Chris Ax, who confessed to the same Ranger, but then had his charges dropped because DNA pointed to someone else.

But as I learn more about Holland I see that he is a hero to a lot of people, and often for good reason. Could he really have messed up this investigation so badly that an innocent man went to prison? In other words: Am I the one messing up?

I’ve been here before. There are always moments, working on a story like this, where you begin to doubt everything you think you know. And there are two elements of the case against Driskill that are still bothering me. I need to look at both of them in more detail.

First, the evidence from the jailhouse informant, the man who says Driskill confessed to him in the yard at the jail. And then the eyewitness, Michael Harden, who says he saw Bobbie Sue Hill being abducted. It was his descriptions that led Holland to Driskill in the first place. How solid were those descriptions?

I’m going to start with the informant, who we’re calling John. In the last episode, we heard how he claimed Driskill confessed to him in the rec yard at the jail.

John: He wasn’t supposed to be around any inmates, because Larry has a bad habit of discussing his case, so we went to rec and we started talking and he actually told me that he did do it.

Driskill said it never happened. I don’t know what to do with that. And it’s a crucial piece of the puzzle, because when Driskill agrees to take the plea deal, he believes that John is going to testify against him.

So I mention the quandary to a journalist in Austin named Pamela Colloff. She’s a friend of mine and a bit of a local legend when it comes to reporting on the criminal justice system. She’s written extensively about jailhouse informants. Pamela tells me, “In lots of cases, this sort of informant testimony is a major piece of why people agree to plea deals: It makes them feel like they wouldn’t win at a trial.” But then she says that John’s story is suspicious, because nobody walks up to a random person in jail and says “Here’s what I was accused of” much less “I did it.” That’s just not a thing.

So why would John have made up this whole story? Well, what if he stood to benefit in some way?

On Pamela’s advice, I start making public records requests and [building] a timeline of John’s case alongside Driskill’s. First, I get the recording of John talking to investigators. And it doesn’t take long to notice red flags. Here’s John:

John: And he told me that he passed a lie detector test by sitting on his legs ahead of time. That caused his nerves to go in some kind of reaction or something to cause him to pass.

His story makes no sense: In reality, Driskill failed a polygraph. If Driskill really did admit to John that he committed the murder, why would he lie about passing the polygraph?

Then, buried in a mountain of documents, I find an email, from a prosecutor to John’s lawyer. It shows they offered John a prison sentence that was likely more favorable than it would have been otherwise, in exchange for telling the story about Driskill at his murder trial.

Armed with this new information, I look for John himself. I find him on Facebook and ask him about what happened. He writes back that Driskill did confess to him. But then he says that in the end, he actually backed out. He refused to testify against Driskill. Why would he do that? That was his ticket to a lighter sentence, right?

He writes back, “I didn’t know enough about his situation.” Cryptic. Then I ask, “Did they offer you any help with your own case?”

He says “Nope.” That’s a lie: I have the email proving it.

But then he stops responding. He ghosts me. The takeaway? We can’t prove John was lying, but his story is really flimsy and he probably stood to benefit from telling it. One more piece of Driskill’s conviction unravels.

But that still leaves one final lead I need to follow: Why was Driskill in the interrogation room in the first place? It all stems from the one eyewitness, Michael Harden, and his description of the man who abducted his girlfriend.

Back in Episode 2, we heard how Harden provided descriptions of the man. He did this twice: in 2005 and 2014. Remember how these two sketches differed a lot.

The old 2005 sketch shows a man with a wide face, strong eyebrows, and a dark mustache. The face in the later sketch from 2014 has slimmed down, the mustache has almost disappeared, and a pair of eyeglasses has appeared from out of nowhere. This second sketch is also age-progressed, meaning they’ve tried to account for how the face would have changed over 10 years.

The vehicle that Bobbie Sue Hill was abducted in also transforms. It goes from a minivan with lots of windows in 2005, to a big work van mostly without windows in 2014.

All these changes are crucial because the later version is arguably a closer fit to Driskill and the van that he once drove. And it was only after seeing this later sketch that Gene Burks, the pawn shop owner, called in the tip to Holland, pointing him towards Driskill.

I decide to try and track Harden down. This time, it takes a lot more than simply sending a message on Facebook. But eventually I find him.

Maurice: How are you doing?

Michael Harden: Alright, how are you doing?

Maurice: Good, good to see you.

Michael Harden: What is this about? My girl? My ex-girl?

Maurice: Yeah it’s about Bobbie.

Michael Harden: Yeah.

Harden is in jail. He’s been arrested on a nonviolent drug charge. I show him the sketches.

Michael Harden: He looks more Hispanic.

Maurice: Do you remember the man, the real man having a mustache?

Michael Harden: I remember him having a mustache.

Maurice: Like this? Or…?

Michael Harden: No, kind of, like, kind of, like…

Maurice: More like me and you?

Michael Harden: Yeah.

Maurice: Like filled out with the beard? I see.

Michael Harden: So that guy looks a lot pudgier. A lot older.

Maurice: I noticed that this guy doesn’t really have any kind of beard.

Michael Harden: No, no.

Maurice: But you said that he did have a bit of a beard.

Michael Harden: Yeah, like a goatee.

Maurice: A goatee? OK, that’s helpful.

Overall, Harden stands by the second sketch over the first. But you can hear that his memory is perhaps even more hazy now. Is it a beard? Is it a mustache? Is it a goatee?

Assuming he’s telling the truth about what he remembers, and not everyone thinks he is, how do we know which memory — which face, and which van — is more accurate?

I need to take a closer look at how the second sketch came about.

Texas Ranger Victor Patton: Five…Relaxing more and more…Four…

Remember this?

Victor Patton: Three, two, one…

This is Victor Patton, hypnotizing Harden before the second sketch.

Victor Patton: Zero. Very good.

Before working on this case, I’d heard of forensic hypnosis, and I imagined it to be something from a long time ago, maybe the 1970s. But the fact that it was used in 2014 really stands out to me. I want to know how useful it is as a technique. Is it possible that it led to a more reliable sketch the second time round?

Journalist Lauren McGaughy: We all think of hypnosis as a truth serum. It's not a truth serum, but we think of it that way because of TV shows and movies where, you know, someone gets hypnotized and then they reveal some deep secret that they were keeping, locked deep inside for a long time.

This is Lauren McGaughy. She writes for The Dallas Morning News. Her reporting has found that forensic hypnosis started in California in the 1970s, and spread across the country. Then, over the next four decades it was debunked by scientists and attacked by lawyers and abandoned in much of the country. But not Texas.

Lauren McGaughy: Texas has kind of held onto it as long as humanly possible, whereas, something like half of the states, as of 2020, had either banned the practice or significantly curtailed its use. Texas had kind of doubled down on it.

And this goes too for the Texas Rangers. They log their use of hypnotism, and McGaughy found records of it being used at least 1800 times over 40 years. But as we know by now, memories are extremely fragile and open to manipulation. McGaughy talked to a lot of psychologists and learned how hypnosis risks changing our memories.

Lauren McGaughy: There is some proof that you are more highly suggestible under hypnosis. Someone can actually create false memories or fill in the gaps of memories with things that didn't happen. If you recall something under hypnosis, people have the tendency to believe that that memory is true even more.

McGaughy found cases in which the stakes were shockingly high. There was a man on death row named Charles Flores. His lawyers said the only reason he was there was because a witness had been hypnotized and then picked him out of a lineup. Flores had nearly been executed. He still might be.

It was actually McGaughy who tipped me off to the Chris Ax case. She also knew about the Driskill case, and she’s highly critical.

Lauren McGaughy: Bringing someone in 10 years after they saw someone drive away in a white van, and having them try to tap back into that memory, is highly problematic. The further away from a memory you get, the fuzzier it gets.

With this context, the fact that Harden stands by his second sketch is not surprising. If it’s more recent, then it probably better matches what’s in his mind. But the details changing like this — it’s such a red flag, suggesting his memory might have been contaminated.

So to recap, the single witness is hypnotized — a process known to risk changing memories — after 10 years where the memory could have been contaminated anyway, and this gives us a sketch. And, by the way, drawing a face from a description? Not an exact science in the first place. One expert told me, “Our facial recognition is worse than we think, and this guy has seen thousands of faces since the abduction.”

But then this all just happens to lead to exactly the right person?

I mean, if Driskill was the right guy, then finding him this way would have been like winning the lottery.

This all leaves me wondering why hypnosis is still a tool police use, when it’s associated with such risks. McGaughy asked a bunch of police about it.

Lauren McGaughy: They said yes, it helped them crack cases or they believed they were cracking cases using hypnosis, and that's all that matters. That was kind of the bottom line for them: Whatever works. But a lot of them, especially the diehard proponents here in Texas, they really, really, truly do believe in it. They spoke about it almost as a religious experience — that you had to put your trust in the tool. And if you did that, and if you pursued your cases in the right way, miracles could happen.

When I spoke to Texas Ranger Victor Patton, who hypnotized Michael Harden, it wasn’t like that. He didn’t pretend hypnosis delivered miracles.

Victor Patton: Hypnosis is a fairly simple process. It's not rocket science.

He just said, “This is effectively a way to get witnesses to relax and carefully dig up their memories, and maybe they’ll remember something new.”

Victor Patton: Hypnosis is a tool. And if done correctly, you don't feed anybody information. Any information you get comes from them. I mean, at the very worst, you get more information than you had when you started, or you don't get anything.

When Lauren McGaughy’s series came out inThe Dallas Morning News, in 2020, it caused such a huge stir. There was a battle at the Texas state house as legislators tried to ban the use of hypnosis, before the governor vetoed the bill.

But McGaughy’s articles did have a serious impact on the Rangers.

Lauren McGaughy: In January 2021, the Rangers formally ended their hypnosis program. They confirmed that they are no longer going to be training individuals in hypnosis and that they will not be using hypnosis in any further criminal investigations.

But these changes? They only look towards the future.

Lauren McGaughy: When the Texas Rangers did away with their hypnosis program, nothing happened to the people who were already in prison and were sent there with the help of hypnosis.

Which means none of this can really help Driskill.

January 14th, 2022, marked seven years since his arrest. And while he’s been stuck in a cell, with his life on hold, he has painful reminders of what he’s missing: births, weddings, funerals. He gets a letter telling him his sister has died.

And his wife decides to move on.

Larry Driskill: ...and then my “Dear John” letter from my ex-wife. Now I can't get used to calling her ex-wife. I've been married for 40 years.

Maurice: What was it like for you, getting this “Dear John” letter from her?

Larry Driskill: I was upset. I cried some, but that's part of life, when I've been with her longer than I'd been single, and you think, what could I have done different or otherwise?

He knows he’s going to get out in 2030, when he’ll be nearing 70 years old. I’m thinking about how Ashley Fletcher, the law student who got the Innocence Project of Texas to take this case, had thought he’d be excited when they visited, but instead she got this sense of hopelessness from him.

Larry Driskill: Anytime I get downtime, you start thinking and sometimes you can't get [my mind] to shut the heck off. All I can think of is the man upstairs’ plan, and he knows I didn't do it, and he'll take care of this in his time.

So by early 2022, the Innocence Project of Texas is trying to test the DNA from the crime scene. In January, I publish an article about the case for The Marshall Project. I harbor naive hopes that the searing power of my reporting will somehow trigger a wave of soul-searching among the Rangers and the prosecutors. But of course, my article is met with silence from the authorities. Driskill is still polite to me, but I can tell he’s impatient.

But then his lawyers, Jessi Freud and Mike Ware, have a realization: All that time passing has actually changed something for Driskill. So much time has passed that he’s eligible for parole — but, it’s unlikely he’ll get it. Driskill is claiming he’s innocent. Parole boards have often been resistant to letting people out early when they make that claim. They want you to say how sorry you are for your crime, and you can’t do that if you’re maintaining that you didn’t commit it at all.

From my point of view, it seems like a longshot. The Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles is famously stingy. I’ve seen them fail to step in even when someone is going to be executed and there is a good chance they’re innocent.

But Jessi Freud has an old friend who specializes in these parole applications, so what the hell? They put in a bid for Driskill. And wait to see what happens.

Jessi Freud: How are you?

Maurice: I'm good. I'm at a seminar in New York.

Jessi Freud: So there's really good news.

That’s next time on “Just Say You’re Sorry.”

CREDITS

“Smoke Screen: Just Say You’re Sorry,” is a production of Somethin’ Else, The Marshall Project and Sony Music Entertainment. It’s written and hosted by me, Maurice Chammah. The senior producer is Tom Fuller, the producer is Georgia Mills, Peggy Sutton is the story editor, Dave Anderson is the executive producer and editor and Cheeka Eyers is the development producer. Akiba Solomon and I are the executive producers for The Marshall Project where Susan Chira is editor-in-chief. The production manager is Ike Egbetola, and fact checking is by Natsumi Ajisaka. Graham Reynolds composed the original music and Charlie Brandon King is the mixer and sound designer. The studio engineers are Josh Gibbs, Gulliver Lawrence Tickell, Jay Beale and Teddy Riley, with additional recording by Ryan Katz.

This series drew in part on my 2022 article for The Marshall Project, “Anatomy of a Murder Confession.” With thanks to Jez Nelson, Ruth Baldwin and Susan Chira.